Ukrainian Katerina Silvanova and her Russian co-author Elena Malisova never expected their book about two teens falling in love would be such a hit – and a reason to flee their countries.

A coming-of-age story about the love that grows between two boys at a Soviet pioneer camp, the book, with its two engaging star characters Yura and Volodya, is popular in Russia.

But following its publication, author Silvanova was forced to flee to her Ukrainian hometown of Kharkiv, despite it being under Russian attack, while Malisova wound up having to begin a new life in Rostock, Germany.

Their first work, “A Summer in the Red Scarf” was dismissed as “perverse” in Russia, amid Moscow’s hostility towards the LGBTQ community.

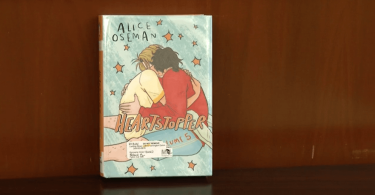

Cover the book A Summer in the Red Scarf, by authors Katerina Silvanova and Elena Malisova. Photo: X@semspoiler

“It’s a simple story about two young people who discover how their friendship gives rise to feelings that they can’t explain at first, and then realise that it’s love,” says Malisova in a video call alongside Silvanova, who joins the exchange from Kharkiv.

The book sensitively explores the love that blossoms between the characters 16-year-old Yura and 19-year-old Volodya, who care for youngsters at a Soviet holiday camp in Kharkiv in 1986.

Neither author went to a pioneer camp, a gathering of young people away from home in winter or summer, in the communist equivalent of a scout camp.

But they drew on the stories and diaries of their parents to bring to life the highly structured daily routines at the camp, where days centre on partisan games, political children’s theatre, appeals and sport.

Russia last year banned the notional LGBTQ “movement” by declaring it to be extremist in what officials said was a fight for traditional values like those espoused by the Russian Orthodox Church in the face of Western influence. Photo: AP

The story also touches on authoritarian upbringing and egalitarianism, themes that the children at the camp encounter during their holidays.

But at the heart of the story are the characters. Yura is very clear about his feelings and makes the first move, while Volodya, who wants a career and is reluctant to accept his homosexuality, fears he will be ostracised within the communist system.

The story was a runaway literary success in Russia in 2021, thanks perhaps to a certain appeal for those nostalgic for the Soviet era.

But for teenagers and adults alike, the attraction was the way the book deals with the universal theme of forbidden love, told with passion.

A fan group soon formed on TikTok. But Russian ultranationalists, fearful of the “Westernisation” of society that they see as emanating from LGBTQ themes, soon sensed it might undermine the government’s stance on homosexuality.

The Kremlin forbids the portrayal of gay relationships in a positive light in front of children, so the work was published with an 18+ rating.

The authors were subject to massive hostility. “Our book probably also served as a reason to further tighten the law banning so-called gay propaganda and also apply it to adults,” says Silvanova.

Elena Malisova, co-author A Summer in the Red Scarf

The state, potentially fearing that everyone could become gay, moved on to completely ban what it terms LGBTQ propaganda and is even scrutinising the classics.

Russia does not ban homosexuality itself but because it cannot be discussed, it is a social taboo.

Those who publicly support LGBTQ rights risk persecution as extremists if they are part of a movement, which has driven many members of the queer community to flee the country.

“Agitation and persecution against us began in May 2022, first in Telegram channels, then the propaganda media got involved and then the politicians too,” says Malisova. “It’s like the first witch being burned at the stake. I am absolutely certain that all this persecution of the book was artificially brought about.”

Ukrainian Katerina Silvanova (right) and Elena Malisova, co-authored of a book about love between two male teens during Soviet times. Photo: Undated handout

Russia has turned into a dictatorship, she says. “Every dictatorship needs an external enemy and an internal enemy,” says Malisova.

Moscow’s external enemy is Ukraine and all the countries of the free world that support it; its internal enemy is the LGBTQ movement, according to the author.

Malisova and Silvanova first fled together to Armenia in 2022 then moved on to Germany and Ukraine.

Malisova is also still afraid in Germany because the Russian authorities have branded her a “foreign agent” which means she is treated as if she were a traitor.

A new law now also allows property to be confiscated from opponents of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and other dissidents in Russia. “I’m afraid that they might take away our flat and put my mother out on the street,” she says.

For co-author Silvanova, Russia is history, though she lived there for eight years and met Elena Malisova there in 2015. “I am now in Kharkiv with my family to support them here,” she says.

That is one reason why she is not seeking refugee status in Germany, she says. She would rather not think about the possibility of Russia taking Ukraine’s second-largest city – though she is ready to flee if she has to.

When asked how they manage to write together, Silvanova answers, “We often say that Lena and I have one brain that is divided between two people.”

They plan further volumes in the series about the love story of Yura and Volodya, and have already published a sequel in Russia. But they were forced to write it in a rush due to the political situation. “We want to fine-tune the language, expand it and extend it to two parts,” says Malisova.

The first book is already available in German, Italian and Polish. Might it appear in Ukrainian one day?

Silvanova isn’t sure. “Many people here in Ukraine speak Russian, the book has a lot of readers here. But Ukraine wants to shake off everything that is Soviet – and the book is also about history,” she says.

“We don’t want our book to be the cause of trouble here. There is already so much hatred in Ukraine.”