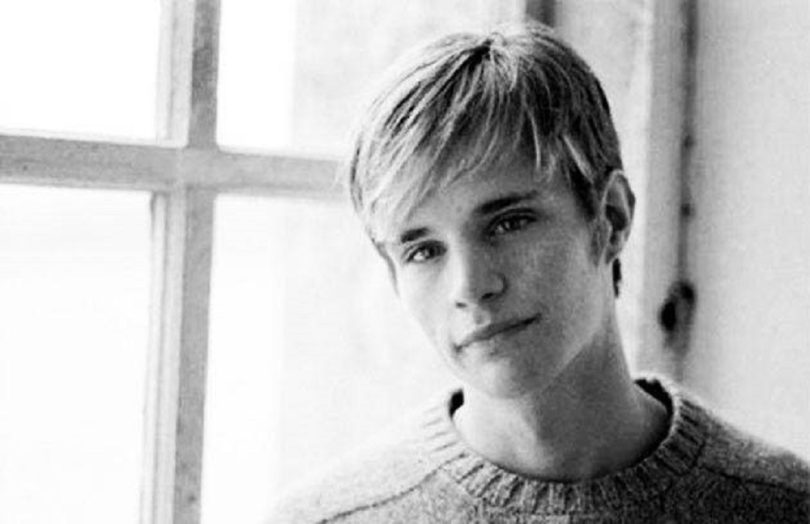

Twenty-six years ago my friend, Matthew Shepard, was murdered.

Matt and I went to college together in North Carolina, but he transferred to the University of Wyoming. In the pre-Facebook world of the 1990s, we passed through each other’s lives with the transience of youth. A few months after I graduated, I saw Matt’s picture splashed across the news.

On the evening of October 6, 1998, two men lured Matt into their truck, drove him outside of Laramie, WY, viciously beat him, and left him tied to a fence in near-freezing temperatures. The next day a passing cyclist found him, but initially thought that his broken and seemingly lifeless body was a scarecrow. Only when he got closer could the biker see that it was actually the slight figure of a man splayed across a rail fence. The only parts of Matt’s face not covered in blood were the streaks that had been washed clean by his tears. Matt suffered multiple skull fractures and remained in a coma until he passed away six days later.

According to testimony given during the trial, the two men convicted of Matt’s murder, Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson, robbed and beat him because of how they “felt about gays.” According to the FBI, roughly 20 percent of all hate crimes are committed based on the victims’ sexuality, resulting in thousands of people being targeted each year simply because of how their assailants “felt about gays.”

Even two decades after Matt’s murder brought anti-gay hate crime to the nation’s attention, crimes against the LGBTQ community outpace similar crimes committed against heterosexuals. LGBTQ students are roughly three times more likely to experience violence in a dating situation and are twice as likely to suffer harassment, both bullying at school and online, when compared to their straight peers.

One in ten LGBTQ students has missed at least one day of school in the last 30 due to safety concerns. Hate crimes against the LGBTQ community are two times more likely to be characterized by violence than by the destruction of property. This disparity in violent versus property crimes is the largest among any protected group.

Eight years ago, one of the worst mass shootings in U.S. history, which killed 49 people and wounded 53 others, occurred at Pulse, an Orlando-based gay nightclub. In the summer of 2019 a Detroit man targeted and shot five members of the LGBTQ community, killing three of them, and a few months later, in two separate incidents, assailants used gay dating apps and social media to contact gay men who were then robbed and murdered. In all of these cases, the victims were targeted because of their sexuality.

Two men killed Matt, but it was the words and actions of many with whom they came in contact that taught them that Matt’s life lacked value, that they could trick him, they could rob him, beat him, leave him to die tied to a fence far from any rescue as the temperatures dropped. However, it is not just the perpetrators of these hate crimes who are taught to devalue the lives of LGBTQ people; the victims hear it too.

LGBTQ is one of the few minorities wherein a member of that community could be sitting next to you at the dinner table and you would have no idea. They could be scooping up a mouthful of mashed potatoes as someone offhandedly degrades something by saying, “That’s so gay.” They smile in group photos even though they just heard a friend call people like them freaks. They hear people they love and respect call gays sick, perverted, and worthless.

These words not only create the Aaron McKinney and Russell Hendersons of the world, but they also explain why, despite making up only 4.5 percent of the population, LGBTQ people account for roughly 20 percent of all suicide attempts. LGBTQ youth are four times more likely to self-harm than their heterosexual peers and five times more likely to experiment with drugs. LGBTQ youth account for 40 percent of the total youth homeless population in the United States. When young people are taught that their lives lack value, they take that lesson to heart.

Nonetheless, even with all of the tragic news regarding the treatment of the LGBTQ community, there is hope. In states where marriage equality was passed, suicide rates among LGBTQ youth dropped. According to the Pew Research Center, 82 percent of Americans say “it doesn’t bother them to be around homosexuals.” Ten years earlier, only 37 percent of Americans viewed gay men favorably and only 39 percent had a favorable impression of lesbian women.

This change should inform leaders in the Republican Party.

While the numbers would probably look rather different if only polling those sitting on RPV’s State Central Committee, a Mason Dixon poll conducted earlier this year reported 53 percent of self-identified Virginia Republicans would support “legislation at the General Assembly this year that would update Virginia’s nondiscrimination laws to protect gay and transgender people from discrimination in housing,” while a whopping 63 percent would support similar legislation in public employment.

This wasn’t a one-off poll. The Tarrance Group conducted a poll a year earlier that found that 55 percent of Virginia Republicans believe discrimination against gay and transgender people in housing should be illegal. This same poll found that 59 percent of Republican voters in Virginia maintain that discrimination in public employment should be forbidden. These are self-identified Republicans, not the general public. These are the voters that our candidates need to actually win general elections, and we are losing them.

Polling numbers of Virginia Republican voters’s support of gay rights are what make the internal fight about what to do about Congressman Denver Riggleman’s decision to officiate the wedding of two of his gay campaign volunteers all the more illuminating.

The back and forth over his possible censure, first within the 5th Congressional District Republican Committee and then the Cumberland County Republican Committee, shows the split within the party on this issue: the party leadership appears decidedly anti-LGBTQ based on the language of the party platform and reaction to Riggleman’s wedding involvement, while Virginians and Republican voters are not.

In fact, overall support for same-sex marriage in Virginia has grown from 35 percent in 2011 (PPP) to over 60 percent in 2017 (PRRI) with only 32 percent of respondents being opposed and eight percent being unsure or undecided. This means only one of two things: either Republicans only make 32 percent of Virginia, or there are Republicans who support the LGBTQ community.

The Republican Party is the party that places the value of human life paramount in its platform. If we are to live the belief, that all lives are precious and worthy of protection, that must include the lives of our LGBTQ brothers and sisters.

However, valuing a life is more than simply allowing it to exist; it is showing care when we speak about people and choosing our language so as to not put people in danger either at their own hands or at the hands of others. On the day that Congressman Riggleman married two men on a hilltop in Virginia, two other gay men from Virginia were beaten by a crowd of 10-12 people outside of a hotel in D.C. Members of the Republican leadership only spoke up about one of these events.

Matt would have been 47 this year; instead, his ashes rest in the crypt of the National Cathedral where they were interred last year. Every year, those of us who knew him pay tribute to the young man who smiles out at us from the pictures of his frozen youth while we watch our own children reach the age he was when he died.

For millions of Americans, the political importance regarding the treatment of the LGBTQ community pales in comparison to the treatment we see our friends and loved ones receive due to their sexuality. This issue is not political but personal. It changes from one to the other the moment someone you love says two simple words, “I’m gay.”

Originally published October 12, 2019. Numbers have been updated.