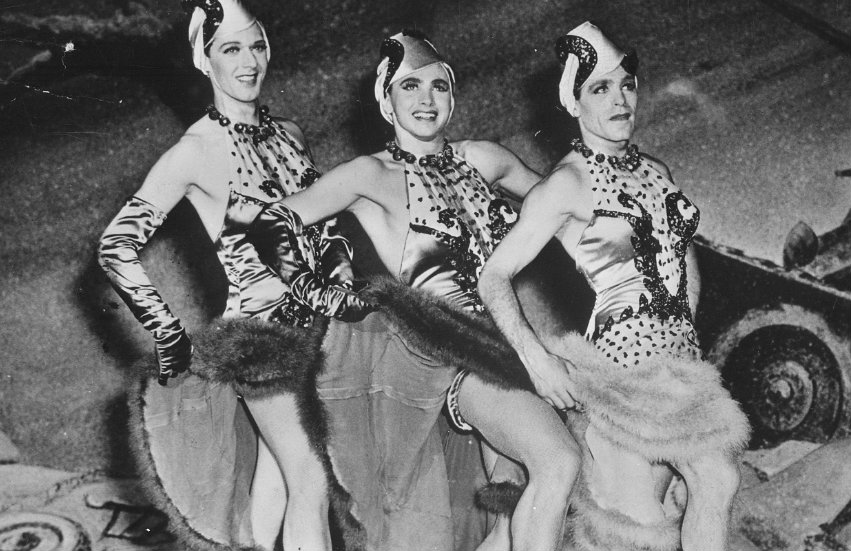

Three soldiers performing This Is the Army in WWII | Photo: Wikimedia/Department of Defense

Today is Memorial Day in the United States, a day to remember those who gave their lives in service of the country.

As trans veteran Charlotte Clymer explained last year, it is different than Veteran’s Day, observed in the US in November.

9/ As a veteran, I am ever mindful that Memorial Day belongs solely to those who paid the ultimate sacrifice. Remembering them is paramount.

— Charlotte Clymer🏳️🌈 (@cmclymer) May 28, 2017

As with every other facet of life, LGBTI people have a presence on Memorial Day, though it may be less visible.

Gay people have served within the US military as far back as the Revolutionary War, before America achieved independence. Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, a German officer, joined Washington’s Army in 1778, eventually becoming a general. He was also most likely gay, according to historians.

How World War II changed life for gay soldiers

World War II was a huge shift for people who served in the military, and also happened to be homosexual.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, servicemen were discharged for homosexual acts. At the onset of WWII, psychiatrists began pushing for mental screenings to join the military, as Allan Bérubé explains in his definitive book, Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two.

Then, in 1941, ‘homosexual proclivities’ for the first time became an official reason for someone to be disqualified from joining the military. All branches, including the Women’s Army Corps, adopted similar measures.

However, as Bérubé writes, between gay men hiding their homosexuality and examiners wanting to let all men in to increase manpower for the war effort, by the end of war, 18 million men were screened and only 4- 5,000 were rejected for their sexuality.

Despite beauracratic discrimination, gay soldiers served the military in WWII in significant numbers.

Drag culture became a saving grace

Passing the screenings to join was only the first uphill battle for LGBTI soldiers.

Bérubé describes the military world as an ‘abnormal environment’ for these people, in that they were surrounded almost exclusively by their own gender. It was an entirely new world to navigate sex, relationships, and stereotypes.

Wartime brought variety shows, which reintroduced female impersonations (previously popular in the earlier part of the century).

One of the most popular shows was Irving Berlin’s This Is the Army. Berlin was a veteran who served in World War I and he staged his wartime musical at Camp Upton in New York, where he was based in WWI.

Another was The Women by Clare Booth, a show that consisted exclusively of female characters.

These drag shows allowed gay men serving to discover a secret culture just for them. It led to important friendships and bonds between these men, as Bérubé explains in his book.

It even helped them improve their camouflage skills in combat.

Countering discrimination with ‘camp’

The military introduced many challenges for gay soldiers.

They had to conduct relationships entirely in secret and often faced discrimination in the form of interrogations and humiliation. Officers sent some to psychiatric hospitals or ‘queer stockades’, as Bérubé reveals.

In order to survive these trials, gay soldiers relied on both each other and ‘camp’.

Performance, drag, and this world sanctioned by the US government for morale purposes, became so much more for gay soldiers as they fought battles both on the field and their own bases.