The Archbishop of Canterbury has claimed that the Church modernising too quickly could lead to “disaster”.

The Church of England has been facing pressure from liberal clergy and parishioners to reform its teachings on LGBT issues, amid fears it is drastically out of step with the public.

The Anglican church has been deeply divided over mooted plans to become more welcoming of LGBT people, with internal discussions spanning several years – and facing threats of rebellions from those opposed to change.

In his speech to the General Synod this week, Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby sent a clear message to LGBT Christians – don’t expect radical change any time soon.

The Archbishop, who has repeatedly kicked confrontations about the Church’s teachings into the long grass, warned that “radical change” could lead to “disaster”.

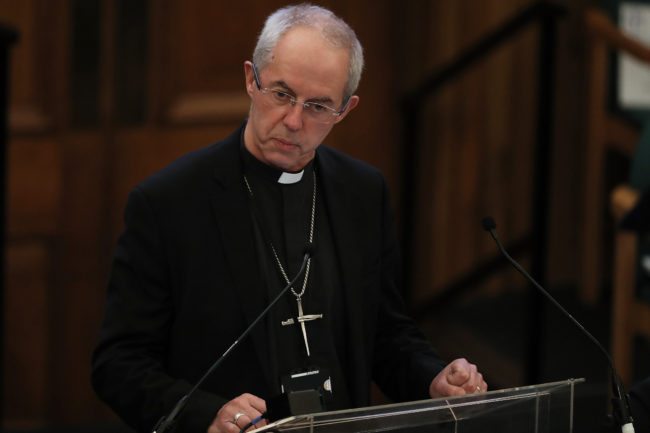

Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby (Photo by ASHRAF SHAZLY/AFP/Getty Images)

He said: “How do we rise to the challenge of change in this generation?

“In times of change, there are two great temptations which afflict all institutions that have long traditions and well-established patterns of action.

“First, there is the ‘throw the baby out with the bath water’ approach. People call for radical change. To call for radical change without being aware of the traditions that underpin and secure the structures to which we belong is likely to lead to disaster, typically through division.

“It stirs fear rather than hope, and encourages a bunker mentality rather than a willingness to see transformation.”

He also warned: “One mistake is to imagine we can change everything and the other mistake is to believe we should change nothing.

“Any tradition that is incapable of adapting is also one that is doomed to death.”

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby (Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images)

Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby (Photo by Leon Neal/Getty Images)

The Archbishop observed: “At one end there are the traditionalists, who feel that even if something has only been done twice before, it must never be changed.

“At the other extreme are the so called radicals who feel that once something has been done twice before, it is high time it was thrown out.”

He added: “If the church is to be available to God it must be understandable to people with whom we minister, among whom we live, simply, whom we love.

“It must stand clearly for its history, live out of its traditions and yet see the promised land and be willing to give all and risk all to get there.

“No institution exists by right, we must re-earn our existence in each generation, that means change.

“But the questioning of ourselves, our attitudes and structures, must be in love, and faithful to the faith uniquely revealed in the Holy Scriptures and set forth in the catholic creeds, which faith the Church is called upon to proclaim afresh in each generation. We must reimagine, but do so improvising afresh in tune with the Spirit.

“If that is truly our aim, we cannot either be traditionalist nor radically abandoning our traditions. We have boundaries and limits set by God himself, to which we are called to adhere out of love for God and Jesus Christ and out of love for one another right around the world, and indeed in love reflecting the love of God for the world itself.

“We have a mission given by God a call to make disciples, from Christ Himself, which must overthrow all particular interests, all personal desires.”

Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby (2-L), and Ezekiel Kondo Kumir Kuku (2-R), Sudan’s newly appointed first archbishop, attend a ceremony in Khartoum’s All Saints Cathedral on July 30, 2017.

Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby (2-L), and Ezekiel Kondo Kumir Kuku (2-R), Sudan’s newly appointed first archbishop, attend a ceremony in Khartoum’s All Saints Cathedral on July 30, 2017.

Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, declared Sudan as the 39th province of the worldwide Anglican Communion and installed Ezekiel Kondo Kumir Kuku as the country’s first archbishop and primate during the ceremony which was attended by American, European and Afrian diplomats, and hundreds of worshippers. (Photo by ASHRAF SHAZLY/AFP/Getty Images)

His comments come amid a broader context of unease within the Church on the issue.

Church of England bishops have been accused of discrimination in recent years, after opting to ‘punish’ gay clergy who enter same-sex unions under hastily-implemented new rules.

And a report that attempted to fudge a middle-ground on LGBT issues was last year tossed out by the General Synod, forcing bishops to go back to the drawing board.

The report made minor proposals to reform to a rule that requires gay clergy to pledge their celibacy, but the lack of commitment to more substantive LGBT reforms was derided as pencil-pushing in light of the church’s continuing archaic rules on sexuality.

Adding to the pile of discontent is a decision last month to reject calls for a transgender ‘naming’ ceremony – upsetting liberals – while affirming that transgender people should be welcome – upsetting evangelicals.

Meanwhile the global Anglican Communion has also been torn apart by a rift between largely pro-LGBT Western churches and hardline anti-gay Anglican churches in Africa and the Global South.

In an attempt to keep the Anglican Communion from splintering, the Archbishop of Canterbury has dolled out ‘punishments’ for the US and Scottish churches, accusing them of making “a fundamental departure from [Anglican] faith and teaching” on gay people.

But the African church bloc is still reluctant to engage fully with the Anglican Communion, and a once-in-a-decade Lambeth Conference was pushed back amid fears of a boycott.

In a recent interview with GQ, the Archbishop warned that divides on LGBT issues were “irreconcilable” and admitted he had handled the issue poorly.

The Archbishop, the head of the global Anglican Church, said: “It is just irreconcilable. There are some disputes that are irreconcilable. I don’t know [where it goes] at the moment.

“What I know is we have to be faithful to the deposit of faith, the tradition of scripture. We have to be holy, above all.

“We have to be people who look like God wants us to look like. When people look at the church they should see Jesus, and really, they don’t very often, particularly when we are totally hostile to people, judgemental, unpleasant, nasty.”

He confessed that his handling of the issue had been poor, saying: “I am having to struggle to be faithful to the tradition, faithful to the scripture, to understand what the call and will of God is in the 21st century and to respond appropriately with love for all people – not condemning them, whether I agree with them or not. That covers both sides of the argument.

“I am not doing that bit of work as well as I would like to.”

(Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

(Photo by Dan Kitwood/Getty Images)

He added: “The generosity I’ve received from gay friends in the midst of not handling this issue very well, and from people who are very traditionalist, has led to me being much less certain than I would have been 10 or 15 years ago.”

But the Archbishop skirted questions about whether he believes gay sex is a sin.

He said: “You know very well that is a question I can’t give a straight answer to.

“I don’t do blanket condemnation and I haven’t got a good answer to the question. I’ll be really honest about that. I know I haven’t got a good answer to the question.

“Inherently, within myself, the things that seem to me to be absolutely central are around faithfulness, stability of relationships and loving relationships.”

When Campbell pointed out that could include same-sex relationships, the Archbishop added: “I know it could be.

“I am also aware – a view deeply held by tradition since long before Christianity, within the Jewish tradition – that marriage is understood invariably as being between a man and a woman, or, in various times, a man and several women, if you go back to the Old Testament.

“I know that the Church around the world is deeply divided on this in some places, including the Anglicans and many other Churches. The vast majority of the Church is deeply against gay sex.”