James Baldwin was an icon who advocated for issues of race, identity, and gender. Join us in celebration of 100 years of the life and legacy of this legendary Black queer author, poet, playwright, cultural critic, and activist.

I discovered James Baldwin’s writings while working as an assistant at the Dallas Public Library after dropping out of college. Newly out and facing parental estrangement and undiagnosed bipolar depression, I sought solace and understanding in the written word. My job was to shelve books, but I usually ended each night taking home more books to read than I had shelved.

One evening, I stumbled upon an essay of Baldwin’s in a Black writers’ anthology. Though I can’t remember the essay’s name, it ignited a passion in me to explore his work deeply. What began as casual reading quickly turned into intense devotion. In a week, I had read Giovanni’s Room, Go Tell It on the Mountain, Another Country, and Just Above My Head in. Within two weeks, I had consumed nearly the entirety of his work and put in a request to special collections for access to the first editions to re-read them, imagining them as purer than the contemporary copies.

Dive deeper every day

Join our newsletter for thought-provoking commentary that goes beyond the surface of LGBTQ+ issues

Baldwin’s works were more than just books; they were a lifeline, a beacon guiding me through the uncertain landscape of my newly embraced Black queer identity. His eloquence and raw honesty resonated deeply in ways I had never experienced before, addressing love, pain, identity, and struggle with unmatched clarity that cut through the noise of everyday life. His insights on race, sexuality, and society were both enlightening and comforting, offering a much-needed sense of camaraderie and understanding.

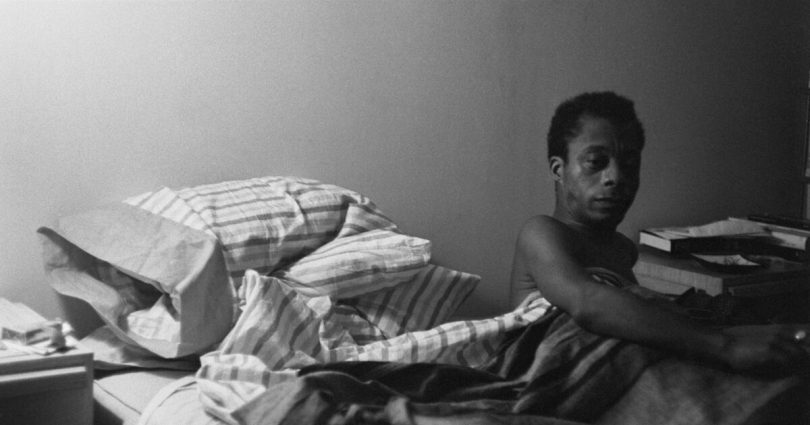

Baldwin became my first representation of a Black queer man who was intellectual, urbane, and revolutionary, and I found myself captivated by his writing. I idealized him as the perfect man for me with his cerebral, cosmopolitan sex appeal. His smile seemed to radiate with the brilliance of a thousand suns. My longing for him was amplified by the fact that I was seeking love for the first time after having to hide my queerness for so long.

My love for Jimmy—as he was affectionately called by friends in life—grew so intense that one day, unable to resist the pull of his image, I tore a page from the introduction of one of his novels. His image became my constant companion, a talisman of sorts. I swooned longingly over it, listening to Sam Cooke’s “You Send Me” and carried it with me everywhere, tucked safely in my journal, often finding myself lost in daydreams as I gazed at it.

Loving a man who, at that time, had been long gone for nearly three decades never once felt strange. I imagined Jimmy and I strolling along the Seine, hand in hand, laughing a little too loudly—as Black Americans sometimes do—in quaint French cafes and reveling in the freedom of being ourselves in the City of Lights. I imagined us as madly in love as Arthur and Jimmy, the couple from his book Just Above My Head.

Imagining a relationship with Baldwin felt completely natural. I believed, and still do, that everyone who reads Baldwin loves him, and while my love may have been deep, it wasn’t unique.

Just Above My Head marked the first book I had ever read that positively depicted love between two Black men. It broke the silence and stigma surrounding such relationships in literature. Arthur Montana, a gospel singer, fell deeply in love with Jimmy Miller, a fellow musician, amidst the Civil Rights Movement. Their story was one of profound connection, resilience, and the courage to be true to oneself. And their relationship endured societal pressures and personal struggles, offering a vision of love that seemed both beautiful and attainable.

In Another Country, Baldwin introduced Rufus Scott, a Black jazz musician whose life was marked by tragedy and racial prejudice. Rufus internalizes his strife, growing isolated from others.

Rufus’s struggles mirrored my own challenges with estrangement and purpose as a Black queer bipolar college dropout. As a young, gifted Black person, I often felt a simmering rage at how society marginalized me. My intelligence was constantly doubted, and I had to prove myself repeatedly, unlike my white peers.

Seeing my own struggles reflected in Baldwin’s characters and narratives validated my frustrations, offering a sense of validation. I had read many authors before, but none were out Black queer men unashamed of their truths. His unapologetic self-expression inspired me to feel equally unashamed.

His writing not only resonated with my personal struggles but also expanded my understanding of the human experience beyond my own age and time, bridging the gap between that and my own sense of isolation. Through his work, I began to see the interwoven nature of humanity’s joys and sorrows and the timeless nature of our quests for love, acceptance, justice, authenticity, and intimacy. His wisdom reminded me that my struggles were part of a larger narrative, connecting me to others who have faced hardship. And in loving him, I felt a profound connection to the broader narrative of humanity.

As I navigated my transformative adolescent and young adult years, dealing with what would later be diagnosed as bipolar disorder, his works provided solace and inspiration. In fact, I often became so absorbed in Baldwin’s novels during bus rides that I’d occasionally miss my stop.

Like countless other racial justice advocates, Baldwin’s eloquent explorations of pain, endurance, and identity made me feel seen and understood, and his activism further fueled my own journey into activism.

On the page, in countless TV interviews, and in the streets, Baldwin was a passionate advocate for civil rights. He participated in the 1963 March on Washington and worked alongside Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. His powerful essays, like *The Fire Next Time* and *Notes of a Native Son,* tackled systemic racism head-on. His activism went beyond Blackness; he was openly queer and proud in a time when homosexuality was still treated as a psychiatric disorder. Nevertheless, he didn’t shy away from talking about the intersections of race, sexuality, and oppression, challenging both Black and white communities to face their prejudices.

Baldwin’s influence has profoundly shaped my understanding of literature and myself, but also the world around us all. His exploration of race, sexuality, and identity offers a powerful guide for embracing one’s true self despite societal challenges.

As we celebrate his 100th birthday, Baldwin’s work continues to resonate deeply with Black queer folks, inspiring pride and sparking conversations about inclusion and justice. We see his influence in George M. Johnson’s memoir All Boys Aren’t Blue and in films like Moonlight, and we witness his kindred passion in Black justice organizing worldwide.His legacy, marked by fearless honesty and visionary insights, continues to provide a lasting sense of belonging and liberation.

His legacy is a testament to the power of words and the enduring strength of the human spirit, and he will forever be a light in my life.

LGBTQ Nation’s sister site, Queerty, has incorporated the intergenerational movement, community, and social platform Native Son as a new channel, which highlights a range of voices celebrating Black gay and queer men. Named after Baldwin’s book, Native Son also commemorates its anniversary since launching on Baldwin’s birthday in 2015.

Don’t forget to share: