LGBTQ Literature is aReaders and Book Loversseries dedicated to discussing literature that has made an impact on the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer people. From fiction to contemporary nonfiction to history and everything in between, any literature that touches on LGBTQ themes is welcome in this series. LGBTQ Literature posts on the last Sunday of every month at 7:30 PM EST. If you are interested in writing for the series,please send a messagetoChrislove.

When I say we need love stories, I don’t mean Harlequin romances (though maybe we need those, too). I mean that, as queer people who must often find new models for our romantic connections, we need stories different from those we saw as kids, the ones that appeared everywhere in television, books, and movies. We need to see other ways love can look, other ways lovers can relate to each other. Probably a lot of heterosexual people need new models, too; there’s no shortage of dysfunctional representations of straight relationships out there. As someone who grew up in the era of John Hughes movies (Sixteen Candles, Breakfast Club, Pretty in Pink), I saw and loved a whole lot of heterosexual romance that was—in retrospect—pretty darn disturbing. But even at their most disturbing, those films showed straight kids that the possibility of love at least included them. The examples were often downright terrible in how the characters treated each other. But as a straight kid watching those movies, you could at least have a sense that, maybe, there was someone out there for you. That it was possible.

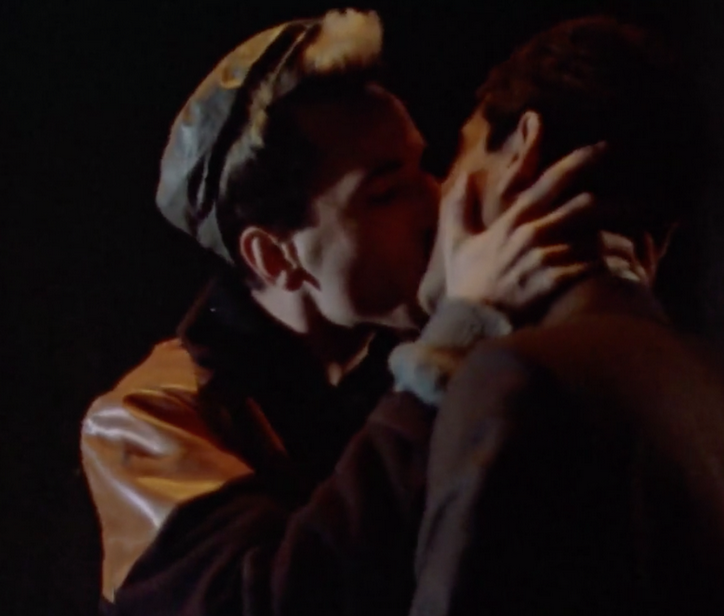

I grew up in suburban Jersey in the ’80s. There wasn’t much in the way of queer love stories around. Once, I caught a bit of the movie My Beautiful Laundrette on late-night TV. I was sixteen or seventeen. I certainly wasn’t out. I flipped onto a scene in which Daniel Day Lewis kisses Gordon Warnecke. They are outside, at night, up against the wall of a brick building – maybe their laundrette. The moment literally took my breath away. I actually gasped. At sixteen or seventeen, I’d never seen an image of—never read one description of—two men kissing. I don’t know that I’d even visualized (fantasized) such a thing. I’m honestly not sure I understood it was possible. Not sex, but this other kind of affection/intimacy. I watched the rest of the movie with the remote in my hand, hyper-alert to flip channels if anyone walked in.

My next experience with an LGBTQIA+ love story occurred in college. I was mostly out by then, but there wasn’t much gay community around. Some dozen openly queer kids on Rutgers main campus. We were a motley group: weird hair, purple or green Doc Maartens, lots of New Wave vibes. There was an “LGBT” student association, but mostly it seemed like we just silently acknowledged each other with our eyes when we passed in the halls, as if to greet out loud would’ve caused straight students to swarm around us with pitchforks. We all knew who we were, though—the connection we shared. I ended up dating one of those kids, a really lovely guy, tall and lanky with a bleached forelock. We had no chemistry, but he was a guy, and we could date—and even fumble around a bit in his dorm room. Once or twice, we went into the city to visit a bar, to see that there were actually hundreds of gay people out there, beyond suburban Jersey.

That spring, my best friend, a queer classmate, gifted me a copy of E.M. Forester’s Maurice. She and I used to affect English accents and have long, absurd conversations in the cafeteria, so maybe that’s why she chose that book. She inscribed it, Vive la difference! (In retrospect, a pretty mature inscription for a nineteen-year-old.) That April, on a warm afternoon, I read the novel lying on a blanket on the college lawn—and realized right there, about two-thirds through, that I needed to break it off with the bleached-forelock guy. I swooned when Scudder insisted on his equality with Maurice: “You called me Alec. . . . I’m as good as you.” I fell in love with Alec Scudder in that passage, and I understood that the guy I was dating wasn’t my Scudder. Wasn’t and wasn’t going to be. Maurice made me feel the magic of romance in a same-sex context, the first time I’d ever felt that; the novel showed me that such magic was possible. I put the book down and went to find the guy for our break-up talk.

So two gay love stories in all my growing-up years. Two same-sex stories versus the flood of mainstream culture, which portrayed gay men as alternately sexless (think campy game-show guest stars) or pathologically oversexed and tragedy-bound. But nothing that looked like love.

Two stories is something. There’s a big difference between two stories and zero stories. But it’s just not enough.

Love as a feeling may be innate, but as a verb, as something we put into action every day in the small and large ways we relate to the people around us, I think it’s learned. And novels, with the novel’s unique power to make a story play out inside our heads, are one of our best teachers.

Have you read a same-sex/queer love story that changed how you think about love, that expanded the range of what seemed possible for you? A novel that showed you options that had, until then, seemed hidden by or even vilified in the dominant culture? Talk about it in the comments!

These days, there are wonderful queer romances out there. For male-male desire, Casey McQuiston’s Red, White & Royal Blue comes to mind, recently made into a Netflix movie, and Less by Andrew Sean Greer. Less won the Pulitzer in ‘18. Our community has come a very long way.

But there are more stories to be written. Stories we need to read, reflections of ourselves—our lives now—and roadmaps for how we can live warmer, fuller, more connected lives; novels to show us how love and family can find us, whoever we are, wherever we are, to give us hope and keep our courage up.

As a fifty-something gay man, there was a love story I needed to read that I couldn’t find out there. Not a novel about young big-city guys, movers and shakers, but a novel about troubled middle-aged guys in small-town America. A novel about people shaped by rough years: who were kids during the intense homophobia of the ’70s, and came out in the ’80s, during the height of the U.S. AIDS crisis. Guys who are wounded and need love (like everyone does), but don’t have the tools to find it. And don’t have a lot of opportunities because of where they live, and carry a whole lot of baggage.

Toni Morrison: “If there’s a book that you want to read, but it hasn’t been written yet, then you must write it.”

My previous books have been collections of poetry. I’ve had a decent run. My book Sweet Core Orchard won a Lambda Literary Award (2009). My last collection, My Husband Would, won the Connecticut Book Award (2021). But there was a story I needed to read that poems couldn’t deliver, at least not poems as I know how to write them.

I present here the first chapter of my new novel, The Spring before Obergefell, which will be published by the University of Nebraska Press tomorrow, October 1st. The book is about middle-aged guys in small-town America. My challenge to myself was this: write a novel with a happy ending that I could believe. A romance, but not a fairy tale. I drafted it during COVID lock down. I live alone, and it was a solace to have the characters to keep me company.

The Spring before Obergefell was selected by Percival Everett for the AWP Award Series James Alan McPherson Prize. Mr. Everett wrote about the book:

“The world of this novel is patiently rendered with language that is direct, unadorned, yet full. The characters are presented with the kind of affection that is rare in much current literature. This is a love story and a growth story and a story about how the world changes and affects our self-definition, confidence, and place within it. The relationships are familiar but not cliché, surprising but not sensational. I love the honesty and openness of this novel.”

The Spring before Obergefell can be purchased here: www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/…:

At checkout, use coupon code 6AF24 for 40% off. The book should be about $13. Less than a pizza!

The opening chapter follows. I hope you enjoy it. Thank you for reading the diary.

—ClaytonBen

P.S.: I’ve been a member of this community since 2005. It’s been my mainstay every election night (on and off years) since then. I look forward to us celebrating together on a breathtakingly blue election night ‘24!

P.P.S: Extra thanks to Chrislove for letting me have the mic today.

* * *

The Spring before Obergefell

1.

If I were straight, or if I lived in one of a handful of cities—really, a handful of neighborhoods—it could happen at a coffee shop. Failing that, it could happen at work. It wouldn’t be a “meet cute.” I’m too uptight for that. But a hello, a recognition that we were connecting in a space of romantic possibility, rather than the usual space between men who don’t know each other, which is more about measuring distance, maintaining boundaries.

Sometimes people just start talking to strangers. That’s how it would happen. He starts talking to me. Complaining. Maybe about the weather because it’s early February in the Midwest. Let’s say we’re in line at the post office, and he says, “Line’s long but at least it’s warm in here,” clapping his gloved hands together, a padded envelope between them. He shows a little bit of tooth, a smile under his beard.

Then I’d have to say something, and I’d want to say something because he’s got a kind, wide face. A little grizzled, wrinkled around the eyes, but bright eyes. I’d want to continue the conversation.

But I wouldn’t be able to think of anything fast enough, and the moment would pass.

No, not this time. That’s the second thing that’s different. Not only are we free from the assumption that we’re both straight, but the moment doesn’t pass. He puts out his hand and says his first name: maybe it’s Sandro or Chris or Jake.

I say my name, shake his hand, and ask how he’s holding up with the snow. I mention that I heard on the news they’re up to eight feet total accumulation this winter in CMH. (The airport code for Columbus. He’d be local; he’d recognize it.) And he says that must be why his back has been sore for the last week, shoveling that much. “That shit weighs a ton.” And I say that it’s my left rotator cuff, that I fucked it up with decades of bad form at the gym, and I really feel it shoveling. The line dwindles as we talk, and soon he’s at the front. He nods at me, then goes up to the counter. While I’m waiting—at the head of the line now—I scribble my phone number on a Priority Mail label and step up to leave it beside him as he watches the clerk weigh his envelope. “Hey,” I say as I place the square of paper, “say hello sometime.”

The Castro. PTown. Parts of New York City. Neighborhoods where that kind of interaction would be possible. They are as foreign to me as if they existed in some other epoch: a Roaring Twenties, a Summer of Love. I don’t live in those neighborhoods, and those neighborhoods don’t live in me.

Though there are gay men around here. Most are out, too; though we are scattered, living on streets we don’t define. We’re not invisible because we’re out, but we’re not quite visible either. On Thursday night, I have one of these men over. He has a partner, and he lives with the guy. He’s a repeat, so he knows to knock softly, to keep his voice down. It’s after 10:00, and my widowed father is in his room. My father’s not asleep; at least I don’t think he is. His light is on. He doesn’t sleep much anymore. It’s not a secret that I have guys over, and what I have them over for, but there’s no reason to make the kind of commotion that would bring him out of his room for awkward introductions. Awkward and unsexy. So when I hear Josh’s car roll up the gravel driveway, I crack the door and wait there for him to walk up. I’ve pulled on a wifebeater and jeans, a getup which I know he likes. And I like wearing it. Josh is a lawyer, thirty-four (if his profile is to be believed), with brown hair and moony eyes—though he’s very much a type A personality. The kind of guy who has all the items on his desk arranged at right angles. He has soft hairless skin, which is not my first choice, but not my last, either.

I open the door wide enough for him to slip in. “Hey,” I say, stepping back so he can enter.

“Hi, sexy.” His voice is hushed. Josh is conscientious, polite.

“Give me your coat.”

He pulls off his gloves, unzips and removes his puffy jacket. Then steps toward me and puts a hand on my chest. Usually we have a little small talk; I find it makes the sex easier. But as I lean in to kiss him hello, another car pulls into the driveway. The headlights are coming straight in the front windows because it’s an SUV and the lights are higher. The blue intensity shines right into the foyer, which is really a screened porch that some previous owner converted into a room. Josh turns his head toward the window, looks out for a moment, and says “fuck.” He says it twice, the second time louder. Then the SUV door opens and slams, and Josh freezes. Someone is walking toward the door, loud steps on the gravel. There’s a sharp series of knocks.

“Gary,” Josh says.

Gary. The guy bangs at the door. Of course he does. He can see us through the windows standing less than a foot apart.

“Do we need to call the police?”

“No, no, just let me talk to him.” Josh goes to the door and opens it, blocking it with his body as he steps out, the screen door smacking against the frame behind him. In a minute, they are screaming. Then I hear my father’s door open.

“What the hell is going on,” my father says, tying the knot of his terrycloth robe as he comes toward me. “It’s almost midnight.”

My father is just a few years shy of eighty, but he gets around well. A little stooped, but plenty capable of raising a fuss. “Who’s out there?” he asks. He goes over to the window and looks out. I assume he sees Josh and some guy screaming at each other.

“Don’t worry about it, Dad, just go back to bed,” I say, waving him off. He doesn’t move from the window. I grab my coat and go outside.

Gary is a good fifteen years older than Josh, salt-and-pepper hair, glasses, thin, and a lot taller than either of us. A good-looking guy.

“Look,” I say, “you guys have got to take this home.” I turn to Gary. “I don’t know what’s going on here. I didn’t realize Josh was breaking any rules, but I have neighbors. You guys have to take this home.”

This is half true. About the rules Josh might have been breaking. I didn’t ask. I pointedly didn’t ask.

Then Gary is moving toward me. I haven’t been in a fight since middle school, when Eric Glickman told me he’d beat me up when we got off the bus at our stop and then proceeded to do just that. That fight was a pretty one-sided affair, with Eric on all fours on top of me, pinning me down, laughing in my face.

Gary throws a fist at me. It lands on my chin, sending a jolt of pain through my jaw and thudding in my skull. I reel back onto the small concrete patio outside the front door, and then he jumps forward, his body rushing against me. I am knocked against the side of the house, but I steady myself and put my hands up. Then Josh grabs Gary, pulling him back, and my father comes flying out of the house. My dad is an NRA Republican. He has a shot gun in his hand.

Gary pushes Josh away from him, and Josh falls back on his ass, right to the ground. Then the guy stalks back to his car. He shouts “Fuck you, Josh” before getting in. I glance around the street, looking for neighbors’ lights that are on, or are just going on.

“Please Dad, get back in the house,” I say.

“What’s going on here?” he says. “What are you involved in?” Then he turns to Josh. “What’s your business here?”

“Look Dad, Josh is a friend, okay. Just get back in the house.”

“Oh my god,” says Josh. He’s still on the floor, a hand on his forehead.

“Please Dad, please, it’s okay, let me talk to Josh.”

My father walks forward down the driveway, out to the street. I go over to Josh.

“Are you okay?”

“I’ll deal with this,” he says. “I just need to think a minute.” Josh walks over to the steps leading up to the front door and sits. My father comes back up the driveway.

“It looks like he’s gone,” my father says. “We’re going to talk about this tomorrow.” Then he heads back into the house. I consider sitting next to Josh, but I don’t want him to stay any longer than he has to.

“Okay,” I say to no one in particular.

“I am so sorry. Gary knows what I’m doing. He knew about this. I don’t know what—”

“I have to go talk to my dad.”

“We’ve been living together for nine years,” Josh says. And now I can see that Josh is crying, so I sit down beside him on the stoop. Then the porch light goes on, which means my father is waiting for me, or worse, watching through the front windows.

“Nine years is a long time,” I say.

It is a long time. I’m struck by that when I say it. It’s more than four times as long as I’ve been with anyone, and I’m fifty.

“I fucked it up,” Josh says. “Totally fucked it up.”

He’s really crying now.

“This happened before, you know. Once before. I told him then that it was just sex, that it didn’t matter. He got it. He seemed to get it. I’ve never seen him do this before, get like this. Gary is a really sweet guy.”

I rub a hand along my throbbing jaw.

“Gay men do this all the time,” Josh says. “I just need to go over this with him again. It means nothing to me. It’s just bodies. This is just bodies. That’s all you and I are right now.” He is pointing his finger at himself and then at me, moving back and forth between us as if we were specimens. “I’ll tell him again, and it will be all right. Gary and I have been together for over a decade.”

“You want a cup of coffee?” I say. I try not to sound grudging.

We’re silent for a moment, and I’m suddenly aware that it’s very cold.

“I’m going to go home,” he says.

“Yeah,” I say, putting a hand on his shoulder. “That’s good. Go talk to him.”

He gets up and heads toward his car. “I’ll text you tomorrow.”

“Just give him a few days to calm down.”

“Yeah, okay. Probably a good idea.”

Then Josh is in his car, and I’m back in the house. There are two wicker chairs in the foyer, and my father is seated in one of them.

He looks up at me, scowling.

“What was that about?”

“Just drama,” I say, shaking my head. “It’s late, I’ll explain in the morning.”

“What kinds of things have you been doing? Is this about drugs?”

“No Dad, no drugs. The only drug I do is ibuprofen. I’m going to go take some of them right now and go to bed, okay? This hurts.” I touch my jaw.

“Put some ice on it,” he says. “Put a steak on it. We’ll talk about this in the morning.”

LGBTQ LITERATURE SCHEDULE (2024)

If you are interested in taking any of the following dates, please comment below orsend a messagetoChrislove. We’re always looking for new writers, and anything related to LGBTQ literature is welcome!

January 28:Chrislove

February 25:bellist

March 31:Chrislove

April 28:Chitown Kev

May 26:Clio2

June 30:Chrislove

July 28:CANCELED

August 25: CANCELED

September 29:claytonben

October 27:OPEN

November 24:OPEN

December 29:OPEN

READERS & BOOK LOVERS SERIES SCHEDULE

If you’re not already following Readers and Book Lovers, please go toour homepage (link), find the top button in the left margin, and click it to FOLLOW GROUP. Thank You and Welcome, to the most followed group on Daily Kos. Now you’ll get all our R&BLers diaries in your stream.