“We already filed a case in a US court in 2012,” says Pepe Onziema, director of programmes at Social Minorities Uganda (SMUG), a Ugandan LGBTQ+ advocacy group that was banned in 2022 but which he says continues to find ways to work. The case – “SMUG v. Lively” – was a federal lawsuit in which SMUG, represented by its US partner Center for Constitutional Rights, accused US citizen Scott Lively of complicity in crimes against humanity for his role in encouraging, inciting and supporting persecution of LGBTQ+ people in Uganda.

Lively, an American anti-gay extremist, had from 2009 helped the development of a draconian Ugandan law that finally came into force in 2023. Although the US court dismissed this case on technical grounds, Onziema says its decision has some encouraging aspects. The court said notably that “widespread, systematic persecution of LGBTI people constitutes a crime against humanity that unquestionably violates international norms”.

Uganda’s 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act not only upholds the criminalization of homosexuality inherited from British colonial times but increases penalties up to life imprisonment and introduces the death penalty for “aggravated homosexuality”, which includes repeated same-sex acts and intercourse with a person younger than 18, older than 75, or with a disability. It also criminalizes “promotion of LGBT activities”, with possible prison sentences of up to 20 years. This law has been strongly denounced by national and international NGOs and UN experts as abusive, discriminatory and contrary to international law. The World Bank has withheld some funds to Uganda.

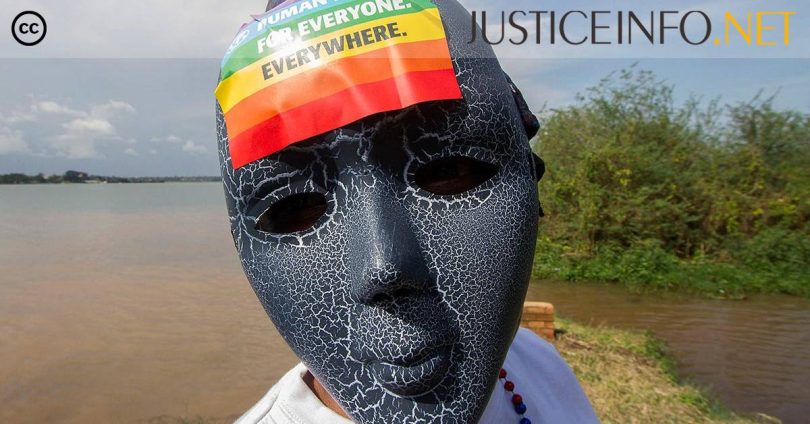

But the law is still on the books. It was signed by 79-year old Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni who, whilst sometimes mitigating his stance, has called for his African counterparts to “provide the lead to save the world from this degeneration and decadence which is really very dangerous for humanity”. Onziema says he has to keep moving from place to place for his own security. Some LGBTQ+ people have fled Uganda.

Judges of Uganda’s Constitutional Court at a hearing following petitions challenging the constitutionality of the country’s anti-homosexuality law, Kampala, 3 April 2024. On the same day, the judges rejected the request to repeal this law, considered to be one of the toughest in the world.. Photo: © Badru Katumba / AFP

“It’s a witch-hunt,” says Kofi Donkor in Ghana, where his country’s lawmakers are trying to follow a similar path. Donkor, who is director of LGBTQ+ Rights Ghana, says his organization, along with others in civil society, have fought hard against a new law approved by the Ghanaian parliament in February this year. Like in Uganda, homosexuality is already criminalized under an old British colonial law which was never repealed. But the new “Human Sexual Rights and Family Values Bill”, while not as draconian as Uganda’s, includes penalties of up to three years’ imprisonment just for identifying as LGBTQ+ and five years for promoting, sponsoring or otherwise supporting LGBTQ+ activities. It also introduces an obligation on families and others to denounce suspected LGBTQ+ people.

This Bill currently faces challenges in the Supreme Court on both technical and human rights grounds, and needs the President’s signature to enter force. As in Uganda, the World Bank is threatening to withhold funds to Ghana on human rights grounds, but Donkor says there is unfortunately strong pressure within sectors of Ghana’s highly “religious and conservative society” for this law to be approved.

He also denounces the influence of Western extreme-right anti-gay groups, especially in the US. This is echoed by ILGA World, an international federation of LGBTQ+ human rights organizations. In the Uganda chapter of its 2023 report it says: “Significant evidence exists which points to the Anti-Homosexuality Act and previous initiatives like it being directed or supported by conservative Evangelical groups based in the United States. Indeed, such lobby groups have been found to have spearheaded much of the anti-LGBTQ+ legislation in Africa, and much of the global ‘anti-gender’ movement.” This does not, it continues, absolve local and national leaders of their responsibility.

Actual convictions or sentences for homosexuality are rare. In Uganda, no-one has been sentenced to death. In Ghana, Donkor says the few rare convictions under the colonial law have been for acts committed with minors. However, these laws are used to attack, harass, imprison and discriminate against LGBTQ+ people. Security forces carry out raids and arrests, often involving violence. The laws have also encouraged vigilante groups and attacks by members of the public.

“One of the things in the build-up to the new law was shutting us down in 2022,” says Onziema. “My executive director and I had personal threats, we had police and politicians harassing us, cyber harassment as well. Two members of our staff are still in court, charged with assault, which is not accurate. They were arrested in 2022, but as part of the harassment of the organization, up to now there is no ruling.”

SMUG fought hard but unsuccessfully against the 2023 law, he says, and this law has only made things worse for LGBTQ+ people. He cites forced evictions of suspected LGBTQ+ people by landlords who do not return their rent; police raids and arbitrary arrests; blackmail and extortion by both law enforcement agents and members of the public; and “conversion therapy”, whereby families take children to medical centres to be “cleansed” of homosexuality. “Usually these conversion therapies are really brutal,” Onziema told Justice Info. “Some of them actually cross over into sexual harassment and sexual violence.”

Then there are anal tests inflicted on suspected homosexuals by police and medical staff. “That heinous violation continues to happen, and it usually happens once the police has picked you up and you are in custody,” says Onziema. “It’s usually forced, they don’t seek consent. A lot of the victims have ended up with really severe mental problems.”

“Individuals within the LGBTQ community are facing lots of hostility within their family, within society and the neighbourhood in which they find themselves,” says Donkor in Ghana. “And then we have evidence, videos of abuses that LGBTQ people suffer. We’ve also faced a lot of discrimination in accessing health care, even in accessing justice.”

“We need, at international level, to turn the whole issue of homosexuality the other way round,” says French lawyer Etienne Deshoulières, who is founder of the Association for Universal De-Criminalization of Homosexuality. “It is not homosexuals who are criminals, it is the people who persecute them. So these people who persecute homosexuals and incite violence, who commit violence themselves – whether they be state or non-state actors – are criminals in the eyes of international law and in the eyes of national justice in countries that recognize the rights of LGBT people.”

His organization has, for example, filed a complaint in a French court against Senegalese Islamic NGO Jamra for online incitement to homophobic hatred. He says the group has a particularly aggressive stance against LGBTQ+ people and has used social media, notably Facebook, to incite violence against them. The French court has jurisdiction, according to Deshoulières, because Jamra’s Facebook page is in French and a large number of its followers are French, or Senegalese living in France.

Then there is the possibility of bringing cases under the principle of universal jurisdiction, for crimes against humanity or possibly torture with regard to forced anal tests. “The UN considers that submitting a person to a test is an act of psychological torture,” says Deshoulières. “France provides for universal jurisdiction for acts of torture, so we could possibly prosecute before French courts doctors or judges who required that an anal test be carried out on a person.”

Then, he continues, there is another possibility. “Another path which is closer in our plans is to bring trials before the International Criminal Court for crimes against humanity against leaders of countries that have policies of deliberate, systematic persecution of homosexuals.” He says his association is working with a law firm in Uganda to build a case, the same law firm that helped SMUG in the US case. Asked if this would be against Museveni, he says yes.

Onziema confirmed that “our legal teams are trying to work on very specific cases”, and SMUG has also reached out to LGBTQ+ activists in other African countries on the possibility of trying to bring international cases. Asked about his hopes for the future, he says the political climate in Uganda is getting worse, “so as a minority community we don’t really see anything positive happening towards our community very soon”. But he is not without hope: “Personally, I’ve been arrested and harassed and assaulted several times and I still live in my country. If there was no community, then there would be no hope for the future, but I live here because I am optimistic that something will happen.”

Recommended reading