I recently watched a YouTube roundtable dinner discussion featuring one gay white male (psychotherapist Matthew J. Dempsey) and four gay men of color (black, Latino, Filipino, and Indian) that touched on an old familiar topic: Is there racism in preference?

The comments, which ran the gamut from ‘It’s wrong to not be attracted to someone based solely on race’ to ‘Why do men of color who prefer white guys criticize white guys for being the same way?’ (both valid points), inspired me to rethink race and desire.

[embedded content]

Few things in life are more complicated than desire. We all fall under its spell at some point, but most of us exert little to no control over the moment it hits or the person on the receiving end of ours.

Can we criticize each other for something over which we have so little power? On the other hand, we may ultimately have minimal say in what our hearts desire, but we have total control over the breadth of its choices.

We make our own menus: If you place strict limitations on what you eat, your meals are likely to be pretty dull. And if you can have sex in only one position, celibacy might eventually prove to be more exciting.

Diversity, like variety, is the spice of life. Even if we love paprika over all other seasonings, there’s no need to ban ginger from the kitchen. That applies not only to food and sex but to the people with whom we have the latter and the ones we fall for, too.

Preference vs. ‘Preference’

That’s why it’s disappointing to see so many gay men qualifying desire with restrictions based on ‘preference.’ And in turn, their abuse and overuse of ‘preference’ has given the word an undeserved bad name.

Preference is a positive that some gay men turn into a negative, often a racially fueled one (‘No Asians,’ ‘No blacks,’ ‘No whites’), using it to keep certain guys out of their dating pool.

If that’s what you want to do, fine. But at least own it by acknowledging what it is. I know plenty of guys of various colors and races who generally date only one type of guy (usually white, sometimes Latino, occasionally black), but that doesn’t mean they’ve rejected all the other spices in the smorgasbord of men.

Just because you have a preference for one thing doesn’t mean you aren’t open to trying other things. That’s what differentiates preference and prejudice.

I have my own sexual preferences. If I were able to create my ideal guy – or at the very least, get him to want me – Mr. Perfect would be tall, dark, and Middle Eastern, probably from Israel, Lebanon, or Jordan.

Meanwhile, half of my boyfriends have been European-descent white and the other half have been South American Latino. But here’s the pivotal catch: Neither my dream guy nor my ex list determines or limits what I am attracted to or what color, race, or nationality my next great love may turn out to be.

When preference ‘becomes a kind of racism’

The problem with preference isn’t preference itself but when it becomes a Berlin Wall, keeping out anyone who doesn’t fit a certain aesthetic, whether it be height, hair color, or race.

When it hinges on the latter, that’s when ‘preference’ becomes a kind of racism. And some gay men use it the way some straight people use religion to justify their homophobia and discrimination.

Thanks, SCOTUS, for setting that dangerous precedent. It’ll come back to haunt us all.

My personal experience with sexual racism, especially during my years living outside of the United States, has all been on the flip side of rejection. It’s been desire fueled by sexual objectification.

Rejection based on race is something I have probably experienced but has always remained unspoken. I’ve been rejected by white guys, black guys, Latino guys, Asian guys, and pretty much every kind of guy. But I’ve never had one of them identify the reason as being my race.

Dealing with rejection

I’m fairly certain it’s been the primary turn-off at times, and not just in the case of white guys who don’t want me. But it’s not my job to police attraction and tell men to whom they can and can’t be drawn.

And not being drawn to me doesn’t automatically make a guy racist. It just makes him not attracted to me. I’ve learned to deal with it and go on.

But I would have a problem with a guy who turned me down not for my own personal qualities but solely based on the color of my skin. And justifying it with ‘That’s just my preference’ would infuriate me.

Preference is a predilection. It’s being drawn to one thing over another. It’s not absolute rejection of ‘another.’

That is why Grindr commands like ‘No fats,’ ‘No femmes,’ ‘No tops,’ ‘No bottoms,’ ‘No oldies,’ and ‘No [insert color, race, or nationality here]’ are so harmful, whether we state them outright or keep them to ourselves.

By falling back on such tried and untrue negatives, we preemptively strike and shut ourselves off from parts of the community based on collective traits. When that trait is race, we earn a spot in another community known as racists.

Digging deeper

I know it’s hard to accept, because just as Westerners are conditioned to appreciate Caucasian beauty as the gold and platinum standard, we’re conditioned to think of racists as the moustache-twirling villains of the old Deep South and Nazi Germany. If it were that simple, racism wouldn’t be so insidious.

Unfortunately, it lurks in corners where it’s not so obvious. The heart may want what it wants, but when desire is dictated primarily by race, we owe it to ourselves to dig deeper and try to understand why.

Sometimes racism hides in the depths of our souls, shrouded by the ‘preference’ we cite in order to avoid having to face it.

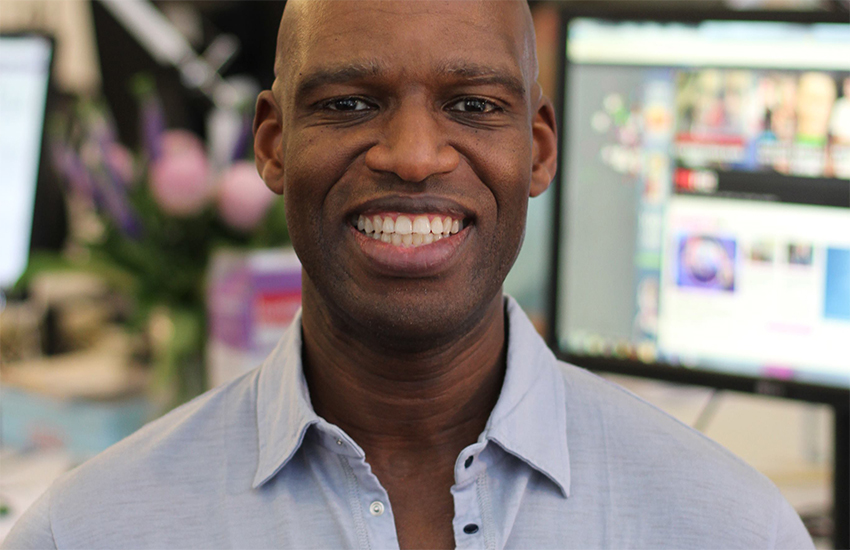

This column first appeared on Medium – reprinted with permission. Jeremy Helligar’s book, Is It True What They Say About Black Men?: Tales of Love, Lust and Language Barriers on the Other Side of the World, is available via Amazon.

Writer Jeremy Helligar (Photo: supplied)