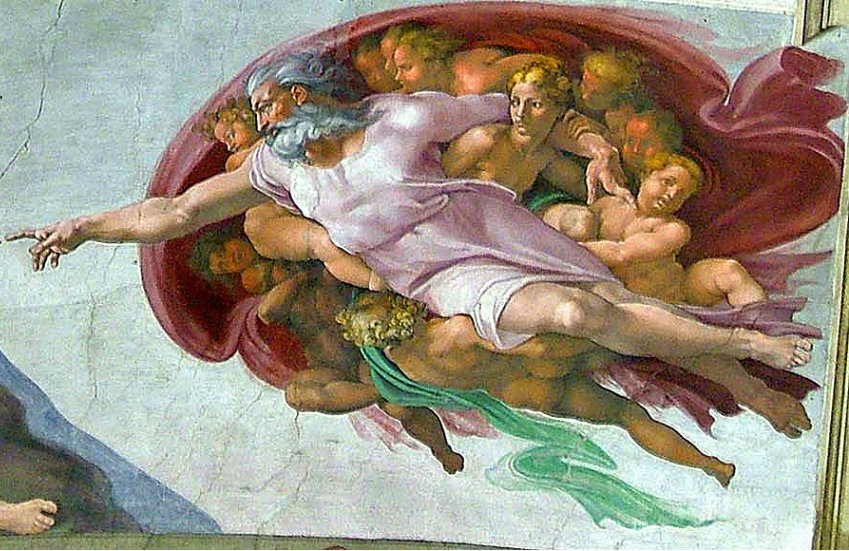

God depicted in Michelangelo’s Creation of Man in the Sistine Chapel | Photo: Flickr/Frans Vandewalle

Leaders in the Episcopal Church this week are debating whether or not to revise the Book of Common Prayer. Specifically, they are looking at gendered language referring to God.

Two resolutions are being considered at the triennial convention for the Church, which starts today (3 July) in Austin, Texas.

The first resolution calls for an overhaul of the Book of Common Prayer, the book used in all Episcopal congregations. It was last revised in 1979.

One of the biggest proposed changes is making it clear that God doesn’t have a gender.

‘As long as ‘men’ and ‘God’ are in the same category, our work toward equity will not just be incomplete,’ said Rev. Wil Gafney, a professor of the Hebrew Bible at Brite Divinity School in Texas, in the Washington Post’s report.

In her own sermons, Gafney added that she sometimes changes pronouns and language. For example, the word ‘King’ instead becomes ‘Ruler’ or ‘Creator’.

Not the only change

There are other proposed changes on the docket for the Church as well.

The Episcopal Church, descended from the Church of England, has been performing same-sex marriages for years. Now members want to formally add it as a practice of their liturgy.

Other members are also calling for a new liturgical ceremony celebrating a transgender person’s adoption of a new name.

Beyond bringing the Church into the 21st Century in regards to gender and sexuality, two more proposed changes include language to advocate for Christians’ responsibility to conserve the Earth and updating the calendar of saints to include figures beyond 1979.

What is the other resolution?

The competing resolution is not for revising the Book of Common Prayer.

Instead, they want members of the Church to ‘intensively study’ the existing book over the next three years.

Chicago Bishop Jeffrey Lee believes they should be looking at the book as it is. However, he does not deny the changing times and the importance of listening to all members.

‘In the culture, the whole #MeToo movement, I think, has really raised in sharp relief how much we do need to examine our assumptions about language and particularly the way we imagine God,’ he said.

‘If a language for God is exclusively male and a certain kind of image of what power means, it’s certainly an incomplete picture of God. … We can’t define God. We can say something profoundly true about God, but the mystery we dare to call God is always bigger than anything we can imagine.’