Russia used to be one of the best places in the world to be gay.

Once slammed as the ‘land of sodomy’ by its western European neighbors, there have been many years in its tumultuous history when many LGBTI people could live freely.

In the 1920s, Russia even became the first country in the world to consider same-sex marriage.

So how did Russia become the largely homophobic nation we know today?

Gay sex as a ‘crime’ in Russia

Lesbian sex has never been a crime in any part of Russia or the Soviet Union. Sex between men, on the other hand, has faced more persecution.

Under the Orthodox Church in the 15th and 16th centuries, sex between men was considered a sin. But even then, believers could use confession and were rarely disciplined.

There was no state law against sodomy until 1716, when Peter the Great decided to westernize the empire. He included a clause against ‘men lying with men’ in his Military Articles, so it only applied to the army and navy. Consensual gay sex led to flogging, while male rape could bring death or life in prison.

In 1832, a sodomy law was enacted punishing civilians with ‘birching’ or deportation to Siberia for four to five years to work in the internment camps.

This was still less strict than many western neighbors. In comparison, England hanged 55 men for gay sex between 1805 and 1835.

After a reform of the penal code in 1903, this was drastically reduced to three months imprisonment. Prosecutions became rare, and a gay subculture developed.

Exceptions made for ‘gay heroes’

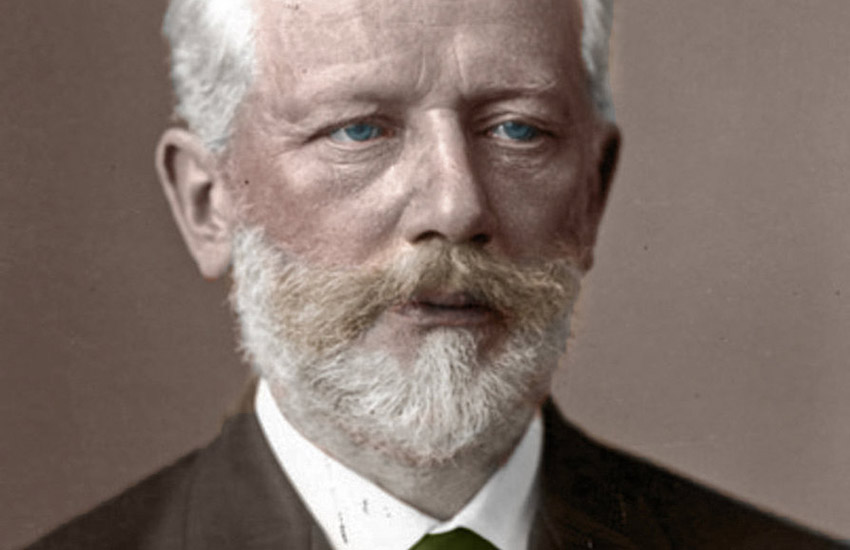

During this time, the country’s greatest composer Tchaikovsky was under threat to be jailed for the ‘crime’ of being gay. But because of his cache, it was unthinkable to arrest the cultural hero. After his death, acknowledgment of his homosexuality was suppressed.

Tchaikovsky’s secret gay history that Russia doesn’t want you to know

Nadezhda Drova, a person assigned female at birth, cross-dressed to fight against the Napoleonic invasion in 1807. When they were found out, the generals gave their blessing to allow them to serve in the army. It was seen as a victory for ‘patriotic duty’.

The first gay novel with a happy ending written in any European language came out in 1906, called Wings.

‘People generally thought within the educated middle class, as it was in Russia, homosexuality was not a big thing. It was tolerable,’ Dan Healey, a professor in modern Russian history at the University of Oxford, told Gay Star News.

‘When you move into the revolution, the socialists that came to power had inherited ideas from European socialism – among those were removing the laws against homosexuality.’

Progressive laws

In 1917, all laws against sodomy were abolished as well as with the rest of the Tsarist penal code.

Intersex people, unusually in the 1920s and 30s, were possibly treated as humanely as they could be in any country in the world. Doctors would trust the intersex patient to make their own medical judgment and help them realize the identified gender.

‘Soviets were progressive about this…and quite relaxed about the sexuality side of it,’ Healey added, ‘Western Europe was anti-surgical adjustments for intersex people.’

It wasn’t as free in Moscow and St Petersburg, as, say, Weimar Berlin during the 20s.

Healey said: ‘Moscow didn’t have the same exuberance. There’s less private enterprise and the regime is ambivalent about sexual minorities.

‘It doesn’t want the law against sodomy, but it doesn’t embrace sexual emancipation either. Gay people understand they have to keep their heads down.’

Queer women, and the idea of two women marrying, flourished

Queer women could fly beneath the radar including legendary poets like Sophia Parnok.

Many of her female lovers were masculine presenting. But, actually, this was an accepted way for a woman to dress in the 20s and 30s.

‘If you were an emancipated Soviet women you dressed more like a man. There was a way of conforming to the expectations of the revolutionary sect by dressing like a butch lesbian. They had that advantage,’ Healey said.

Parnok’s poetry was not political. At the beginning of the 30s, big publishers were shut down and you could only get printed if you went through the state. This meant much closer censorship.

A meeting in September 1929 was held among public health officials, psychiatrists and doctors to discuss homosexuality.

‘They wrote to propose that a woman who dressed masculine or similar to a man should be able to marry their female partner,’ Healey said.

‘They were, in a sense, proposing a form of same-sex marriage. It shows the kind of imagination that the Revolution had stimulated.’

Stalin brings back homophobia

But the onslaught of homophobia was coming with the rise of dictator Joseph Stalin.

Healey noted: ‘In 1933, there was a conversation among the top of the Soviet regime, led by Stalin, who was consolidating his power as a dictator. There’s a crisis in the cities, as there isn’t enough houses or food and they’re trying to sort out who belongs in each city and who doesn’t.

‘Soviet leaders claimed there were wads of gay men who appeared to be conspiring in groups together, and they recommended a law against sodomy so they could put these people in prison.

‘Stalin enthusiastically agrees. They begin the crackdown on minority groups in an attempt to control the chaos they had created with their economic policies.’

There was backlash to this.

Harry Whyte, a communist party member and journalist originally from Scotland, had formed a relationship in Moscow with a man who was arrested by the police during the first wave of arrests in the winter of 1933. He wrote to Stalin and complained about the new law.

‘His letter is 4000 words long and is a discussion how Stalin is wrong in Marxist terms and arguing how gay people deserve protection in a socialist system. It’s a learned and passionate argument,’ the professor added.

‘Stalin didn’t respond directly. He did, however, write on top of the letter “An idiot and a degenerate”.’

The dictator had Whyte removed from the Soviet Union. The journalist returned to Scotland and campaigned there on leftist causes.

Misery in the Gulag

Thousands of LGBTI people during this time were sent to the Gulag, the Siberian internment labor camps where most froze or starved to death.

The queer men and women were very visible there. Survivors wrote how women often toughened up and became ‘butch’ as a way to survive. Effeminate men would play the ‘partner’ to a tougher and more masculine man.

Vadim Kozim was a Soviet pop star who made 17 hit records in the late 1930s and early 1940s. He was a romantic tenor singer in a very political musical landscape.

One of his queer hits involved lyrics about the ‘importance of male friendship’. Marc Almond, of Soft Cell, did a cover version in 2009. Kozim was arrested and sent to the Gulag.

After Stalin had died, Kozim attempted to restart his career.

‘He could do some tours but was rearrested on homosexual offenses in 1969,’ Healey said.

‘He lived until about 1994 in a remote town he was exiled to by the Gulag.’

Sergei Parajanov, the bisexual film director, irritated leaders because of his extravagant and camp art films. One, The Color of Pomegranates, is still famous.

The director was arrested twice on homosexual offenses in the 70s.

The 80s, 90s and modern Russia

Tilda Swinton stands in solidarity with the LGBTI community in Russia

Like around the world, the LGBTI movement exploded in Russia in the 1980s. With the wake of democratic reform, Russians were making their voices heard.

Gay and lesbian newspapers were produced, especially in the 1990s, including in some tiny far away places in Siberia. At the time, it felt like Russia would be like many other countries and give more rights and recognition to the LGBTI community.

And they did, to a point. Homosexuality was decriminalized in 1993.

But then the Putin era stifled progress. Queer newspapers disappeared and homophobia got stronger. Censorship grew, ultimately leading to the enactment of the ‘gay propaganda’ ban in 2013.

LGBTI people have long been a part of Russian history and form an integral part of Russian culture.

‘Tchaikovsky was gay. Sophia Parnok was gay or bisexual. There are lots of examples from culture, literature and other parts of history,’ Healey said.

‘It’s why the Russian internet regular has made LGBTI groups take lists of famous historical LGBTI icons of their websites, because it shows to young people who reads them it’s possible live a gay and successful life as a Russian.’

And Healey has a strong message.

‘Russia will never suppress homosexuality and gender variance. These things will always emerge one way or another.’

Professor Dan Healey is the author of books such as Russian Homophobia from Stalin to Sochi and Homosexual Desire in Revolutionary Russia.