CNN

—

When Emma-Jane Nutbrown went on a family vacation to Jamaica last year, she did so with one condition: that everyone donated to an LGBTQ charity once they got there.

Nutbrown felt uncomfortable with her parents’ choice of destination. Same-sex sexual activity between men is against the law in Jamaica and carries a maximum jail term of 10 years with hard labor. Both Nutbrown and her brother, Simon – whose 40th birthday the family was celebrating on that trip – are gay.

“It made Simon uneasy going there, but most people like to travel for the place, not the politics behind it, so we couldn’t really hold my parents accountable,” says Nutbrown, founder of Queer Edge, which creates safe spaces for the community in London. “I won’t refuse to travel somewhere with family, but I will raise it. So instead of us refusing to go, Simon made everyone donate to a charity out there as his birthday present.”

Nutbrown and her brother are some of the millions worldwide who have an extra layer to consider when booking a vacation: Will they be safe in the destination, and how are local members of the LGBTQ community treated?

“I’m predominantly against it [travel to destinations where homosexuality is banned], but I’m pragmatic. It’s not as easy as ‘Don’t go,’ ” she says. “If there was a shared consensus across the planet [to boycott destinations] then it would work, but I think it’s a lot more complex.”

There are 62 countries worldwide that still criminalize (or de facto criminalize) homosexuality, according to the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA), which counts UN member states. The Human Dignity Trust counts 64.

Of these, 12 could potentially impose the death penalty for same-sex activity, including tourist favorite the United Arab Emirates; Qatar, whose airline was this week deemed the best in the world; Nigeria, which welcomed the Duke and Duchess of Sussex in May; and Saudi Arabia, which last year claimed that it welcomed LGBTQ travelers.

Many people – even those outside the LGBTQ community – simply will not travel to countries where homosexuality is illegal. Corey O’Neill, an office manager from London, is one.

“Safety is at the forefront of anyone’s mind when traveling,” he says. “Even if you’re not visibly queer, there’s an innate danger that how you act might be perceived as gay, which entails not only formal punishments, but police brutality, hate crimes, the general atmosphere. I don’t want to have that in my mind on vacation.”

O’Neill’s stance means that unless laws change, he will never see the pyramids (Egypt has de-facto criminalized homosexuality with jail-term punishment); sleep overwater in the Maldives (up to eight years jail-time plus 100 lashes); take a Kenyan safari (maximum 14 years imprisonment); see Red Square (Russia designates the LGBTQ movement – even displaying a rainbow flag – as ‘extremist’ with up to 12-year sentences); or stop over in Qatar (up to 10 years in prison, with “no legal certainty” over a potential death penalty).

But he’s OK with that. “Why would I give money to a country that doesn’t want me to exist? Even if $10 went towards a tax that actively harmed people, that’d be my money I gave them.”

It’s not just LGBTQ people who feel this way.

Members and allies of the community are currently in their 10th year of boycotting the Dorchester Collection hotels, owned by the Brunei Investment Agency (part of the Ministry of Finance and Economy), since the country introduced laws authorizing the stoning to death of LGBTQ people, as well as the public flogging of women for adultery. In 2019, George Clooney wrote of the importance of boycotting.

But while a boycott may be possible against a business, some feel that swerving an entire country harms the local community even more.

“It can cause a very visceral reaction in people, but there are 50 shades of discrimination, and the challenge is where you draw the line,” says Darren Burn, founder of inclusive travel companies Out of Office and TravelGay.

“Would you go somewhere you can’t get married, or can’t go into the army? The reality is there are loads of places where, even if it’s not illegal to be gay, there are challenges. I totally respect that some people don’t want to support an economy where [homosexuality] is illegal. But the other side is that I want to go, and by going, I’m helping to change mindsets. Every country has gay people. We hear from staff members and locals in destinations, who say, ‘Please come.’ ”

Burn never planned to enter the travel industry. He was a journalist when he went on holiday to Sharm el-Sheikh in Egypt.

“I was in my early 20s, and I was a bit naïve. It was Sharm – a tourist haven,” he says.

“I was traveling with my ex, and we weren’t allowed to check in. We had to go to another hotel. I thought, that shouldn’t happen to anyone, ever.” In 2016, he founded Out of Office, building a contact book of “welcoming suppliers and tour guides.”

In recent years, destination marketers have become more vociferous in attracting LGBTQ clients. There’s usually a financial reason behind it, says Burn. Travelers from the community “are less likely to have children and more likely to have disposable income. They’re loyal customers and trust word-of-mouth referrals.”

Sherwin Banda, president of luxury safari provider African Travel Inc says that the LGBTQ community has “the largest disposable income of any other niche market.”

“A destination’s reputation as being LGBT-friendly is a primary motivation for us,” he says.

A 2021 report from nonprofit Open for Business showed that Caribbean nations outlawing homosexuality saw their GDP hit by up to 5.7% and lost the tourist industry $423 million to $689 million annually.

In Jamaica, tourism officials have tried to downplay the impact of the island nation’s laws against homosexuality.

In 2022, legislation was repealed in Barbados, Antigua and Barbuda, and St. Kitts and Nevis. Trinidad and Tobago had already decriminalized same-sex relations in 2018; in April 2024, Dominica followed suit.

“The Caribbean is moving quite quickly,” says Burn, who adds that the anti-homosexuality laws in many Caribbean and African countries were established under European colonialism.

Banda, who is South African, agrees. “Colonial laws combined with stringent religious beliefs have prolonged a stigma attached to homosexuality across Africa,” he says.

However, he is still comfortable arranging safaris for LGBTQ travelers.

“Once we know travelers are from the community, we take great care to ensure guides, hotels, all the touchpoints throughout the journey are safe for them, but also inclusive,” he says.

“Nobody will say, ‘Do you need two beds?’ We ensure our clients don’t have to come out again to everyone they meet in Africa.”

The experience on the ground is often different from the letter of the law. As Burn says, “It’s also illegal to drink alcohol in the Maldives, but all resorts have it.” (He advises not holding hands at the airport, however.)

In 2020, Bilal El Hammoumy and Rania Chentouf launched Inclusive Morocco, the first LGBT-founded tour operator in a country that punishes same-sex activity with up to three years in jail.

“Being members of the community, we felt we would understand better how to approach it,” says El Hammoumy. “Morocco is a country where tolerance is practiced but not preached.

“We could understand clients’ fears, but on the other hand, it was important to create a space where the local LGBT community can be involved in training programs and hiring opportunities.”

El Hammoumy says that in Morocco, “the reality is a bit different from the law.”

In the early 20th century, cities such as Tangier were “gay heavens” for creatives escaping conservative Western countries. One of Marrakech’s main sights is the Majorelle Garden, where the ashes of former owner Yves Saint Laurent were scattered by his former partner, Pierre Bergé.

El Hammoumy says that Moroccan hotels are generally accepting of same-sex couples, but those they work with have extra training to ensure travelers are comfortable. Some guides have opted not to work with them when they explain their clientele, he says.

However, he says that visiting destinations can change mindsets.

“A lot of anti-LGBT feelings come from prejudice and a lack of education, and direct contact can change preconceived ideas about the community,” he says. Burn agrees.

There’s the economic incentive, too. Banda, who grew up under apartheid, believes that South Africa would not have changed without economic pressure from the wider world.

“Travel does something no other industry can do,” he says. “Africa is heavily dependent on tourism dollars. We can advocate for inclusivity with partners who are prepared to actively welcome our guests. If we stay away, we lose that opportunity to use our voice.”

Does that mean every country should be showered in travel dollars in a bid to change opinions? Not according to these experts, none of whom would send a client to Saudi Arabia.

Uganda is another sticking point – its 2023 Anti-Homosexuality Act legalized the targeting of the LGBTQ community in myriad ways and even carries the death sentence.

“As a company, you need to stand for something, and Uganda advocates for brutal violent acts against gay people. We cannot in good conscience send people there,” says Banda.

Michael Kajubi has a different perspective. In 2013 he founded McBern Tours, curating Uganda tours, after being fired from his previous job because of “suspicions” that he was gay.

“I had to start a company to employ myself and people like me who could not get jobs because of who they are,” he says. The majority of McBern staff are LGBTQ, and all profits go to the McBern Foundation, which supports elderly Ugandans and marginalized youths.

Kajubi – who left Uganda four years ago because of his activism – says that he is still comfortable sending LGBTQ travelers there, as long as they “respect the laws – don’t wave their rainbow flag all over the place.”

All the hotels that McBern uses – even for straight guests – have been carefully vetted as LGBTQ-friendly, says Kajubi. He believes travelers should still visit these destinations but be vigilant where their money is going. He suggests looking for tour operators affiliated to the IGLTA, so that you can be sure you’re not funding inequality.

Boycotting leaves the local community stranded, he argues. Companies that have stopped working with McBern because of Uganda’s anti-gay legislation “have a valid point, but supporting local companies can bring change. You’re paying salaries for people who wouldn’t otherwise be employed.

“If people don’t come we can’t support [Foundation] beneficiaries with healthcare, tuition and basic needs.”

Of course, discrimination isn’t confined to countries where homosexuality is illegal.

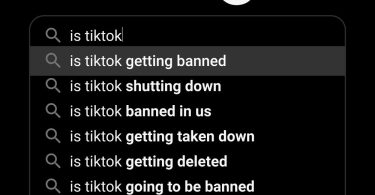

For starters, over 500 anti-LGBTQ laws were introduced in US state legislatures last year alone. In May, the US State Department issued a worldwide alert about potential attacks on LGBTQ+ people and events.

In 2014, Matthieu Jost founded MisterB&B, an LGBTQ travel community with 1.3 million members, after an Airbnb host in Barcelona made it clear that he and his partner were unwelcome. Previously, a French hotel had refused him and his then-boyfriend a double bed.

“This kind of discrimination is all over the place, even in 2024,” says Jost, who won’t even hold hands with his partner in Paris. Banda won’t do that in Los Angeles, either.

For Jost, traveling to a country where homosexuality is banned means abiding by local rules. MisterB&B users are not allowed to book travel in a country with the death penalty for same-sex behavior. In a destination where it’s illegal, users are flagged before booking.

“We warn travelers they need to be cautious. Ask for separate beds, don’t show personal gestures, let family know where they’re traveling and have the embassy contact,” he says.

“If you really want to go there, you need to respect the laws and religion of these countries and play the game.” Burn adds that booking with a specialist is essential – his staff have mystery-shopped mainstream tour operators and found them lacking in knowledge, he says.

For O’Neill, and many like him, it’s not enough.

“I know it limits where I can go – I’ll probably never see the pyramids or go on safari. But there are so many beautiful places in the world that support queer people. That sounds like a much nicer vacation to me.”