I saw the therapist’s facial expression before I heard him speak: “Oh,” he said slowly, eyes avoiding mine. “I didn’t know you were a, uh, homosexual couple,” he managed to say. I had never been referred to before with that word, that “h” word. For a split second, I almost thought he was speaking to someone else.

My partner and I froze. We had been looking for a therapist who took my insurance and had been given a list of names—his was first on the list. We had completed all of the paperwork and even prepaid for the session. Yet, here we all sat looking at each other.

“Uh,” he began again, clearly uncomfortable at the idea of having two women in a couple’s session that he had clearly assumed would be a heterosexual couple.

“Let me give you some referrals,” he said, reaching for his phone.

The need for culturally competent treatment for LGBTQ clients

When I began my education, I had no expectation of going into private practice to “specialize” in working with LGBTQ clients. What was there to specialize in? I would have thought. We are all just regular people. To “specialize” in us seemed pathologizing.

My experience of going to therapy with a female partner opened up my eyes to how unnecessarily and impossibly difficult it was to find a culturally competent therapist. I then started having conversations with friends and even colleagues who were also Queer, many of whom were trans or gender diverse, and found that this was a common experience. What we needed was not someone who saw us as Queer, but someone who saw us as Queer and also understood that that was not the only part of our identity. Someone who knew the ways that these experiences could be unique to us, but who could support us in a judgment-free way without our gender and sexuality being an ever-present elephant in the therapy room. We were still part of a relationship, with all of the interpersonal stressors and struggles that come with being in a partnership as a human being.

It was then I began the foundation for my private practice. At the time, I was working in a hospital setting doing case management and group therapy, but I knew I was needed elsewhere. Because where I was living had only a couple of therapists working with Queer clients, I was immediately “in demand,” showing me I had made the right decision.

This was over a decade ago. Since then, many therapists have built their practice—and their brand—on serving the Queer population. And while I am not as “in demand” anymore for this specific niche, this is a good thing for Queer people who need support. But, we’re not there yet. While I find that LGBTQ clients today have a lot more options for therapists and service providers, there is still a lack of understanding of how specific traumas, such as IPV, manifest in Queer relationships.

LGBTQ relationships have additional vulnerabilities that clinicians need to be aware of

Traditional notions of domestic and intimate partner violence (IPV) often center around heterosexual relationships, which can lead to a lack of understanding of the additional vulnerabilities and risks faced by LGBTQ survivors2.

By focusing on the unique factors present in diverse relationships, practitioners can develop more inclusive approaches that resonate with those experiencing relationship trauma and abuse, ultimately leading to better outcomes for those clients who seek support1.

As clinicians, it is essential to understand the different elements present in LGBTQ relationships. In my trainings on this topic, I address six key areas that are crucial for effective support:

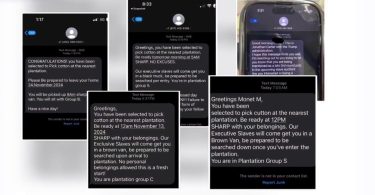

1. Stigma and discrimination: LGBTQ individuals face societal stigma and discrimination, which can exacerbate the challenges related to IPV. Fear of being outed or facing backlash can prevent victims from seeking help, creating a feeling of isolation and hopelessness. With the increase in laws targeting trans and gender-diverse individuals, especially youth, many are scared to disclose their abuse for fear of outing themselves to their families, schools, and communities. The fear of being outed or further victimized can prevent individuals from seeking help or disclosing their experiences. As one of my clients put it: “I have to choose between the abuse I know in my relationship or the abuse I don’t yet know after this forces me to come out in my family.”

2. Unique power dynamics: In LGBTQ relationships, power dynamics may not conform to traditional gender roles. Both partners may experience societal pressures differently, which can lead to unique forms of control and manipulation that are not typically seen in heterosexual relationships. Medical professionals and law enforcement are often trained to look for traditional gender norms when it comes to violence, ignoring the ways that abuse and power dynamics can take place across gender and sexuality spectrums1.

3. Lack of awareness—or availability—of resources: Many support services are designed with heterosexual relationships in mind, tailoring their resources to cis women, with a lack of culturally competent services for trans survivors, male survivors, etc.3 As a result, LGBTQ individuals may find that resources do not adequately address their specific needs, leading to a lack of tailored support and understanding from service providers. Many of my clients have reported that they are unable to get police or medical professionals to take them seriously due to biases and gender stereotypes.

4. Intersectionality: LGBTQ individuals often navigate multiple identities, such as race, class, and disability, which can compound their experiences of IPV. For instance, a Queer person of color may face discrimination based on both their sexual orientation and their race, complicating their experience and access to help.

5. Isolation within the community: While LGBTQ communities can provide vital support, they can also perpetuate harmful norms around relationships. Victims may fear that reporting violence could lead to ostracism from their community, thus keeping them trapped in unhealthy situations.

6. Normalization of violence and abuse: Because many Queer survivors of IPV have also experienced violence in their families and communities, they may have difficulty recognizing abusive behaviors as problematic. Many of my clients, myself included, were raised to ignore or excuse abusive behaviors, which leads to difficulty in recognizing that you deserve better.