Pride festivals are an opportunity for LGBTI people and allies to come together, celebrate or demonstrate. However, not everyone is a fan of them.

A recent column on Them explored the reasons why some gay men hate pride parades. The writer suggested the reasons gay men hated them were often rooted in internalized homophobia. Hating such festivals is similar to denigrating those they perceive as too femme or letting the side down.

However, although that may be true for some, it’s only part of the story. And it certainly doesn’t apply to everyone.

We asked our followers on social media why they don’t attend Pride festivals. Below are just a few of the responses.

Their reasons fell into a handful of related categories.

Drag queens at Birmingham Pride in England in 2017 (Photo: David Hudson)

1. It’s become a ‘circus’

Lots of those who don’t like Pride have an issue with the way some participants dress. Or they think attendees party just a little too hard.

‘It’s a circus and has no relevance to its original purpose,’ says Sez Robbins – a sentiment liked by many on Facebook. ‘Most of those in attendance have no idea what previous generations went through!’

This was echoed by Perry Gentry: ‘Too much of a circus, too many tourists, too much drug use and drunkenness, and frankly I didn’t see what gyrating half-naked gym bodies on floats has to do with Pride for those of us who are average.’

‘Because people turned what those who fought for back in the day into nothing but a chance to walk around half naked and into a sideshow,’ says Steve Early. ‘It’s not Pride it’s a disgrace. You can have pride and not need to show your ass in the streets.’

‘The Parades started in my city as a Dignified March where nobody tried to grab attention. It has evolved into a widespread public drag show and freak show,’ says Herb Williams.

‘Because they are very “gay” stereotype and don’t portray the majority of us that just get on with life without having to parade around in next to nothing. Also being adopters, the things you see are not always appropriate for children,’ says Mark AW.

Singer Anitta performs for Sao Paulo Pride 2018 (Photo: @Anitta | Instagram)

Listening to complaints

Andrea Arnot, Executive Director of the Vancouver Pride Society (VPS) in Canada, is sensitive to these criticisms. She believes all festivals should regularly survey people on why they might not attend.

‘VPS definitely heard through our consultations, that many people felt that Pride events were all just about alcohol consumption and partying.

‘In 2016 and 2017, VPS partnered with Last Door Recovery to provide sober chill spaces at our large party-style events. We have also partnered with Karmik (a harm reduction organization) to provide educational resources about safer partying and harm reduction activities.

‘VPS has been able to modify or add events to our roster that will appeal to a wider variety of interests and needs. We have expanded our Pride Sports Day at Second Beach to be family friendly and appealing to non-sporty-type people too.’

‘We also recognize that VPS events won’t appeal to everyone and that other queer groups create and produce events across the city that meet other needs. VPS has an annual fundraiser, our Unicorn Ball held in February … 100 percent of the proceeds go to a bursary program.

‘Community groups can apply to the bursary program to implement their own events or fund their participation in Vancouver Pride Society events.’

Birmingham Pride, England, 2017 (Photo: David Hudson)

2. It’s become too corporate

The other often-repeated complaint was that the bigger festivals tend to rely on heavy corporate sponsorship.

‘I attend neighborhood Pride Events like Bushwick Pride, Queens Pride and Brooklyn Pride. I am going to avoid “NYC Pride” this year as too commercial, too many banks, pharmaceutical companies and insurance companies and too long,’ was Tom Burrows solution.

‘Pride lost its way years ago. It’s supposed to be an affirmation of our sexuality and a respectful and respectable stance for equality and diversity. It’s just a big business enterprise designed to raid the link pound,’ says Facebook user Tim Mills.

‘And for many who attend it’s simply a chance to push their sexual activities at the general public in a near obscene manner, from their position of privilege. Based on the simple fact that if anyone complains they cry homophobia.

Mills expanded on his comments to GSN. He said Pride has gone from affirming sexuality to being a corporate moneymaker.

Leather men at Pride in London, 2017 (Photo: David Hudson)

‘Whilst I totally accept that people have the right and need to be themselves, there is an apparent attitude that the LGBT+ community can get away with overt sexual behaivour in public that would get any other person arrested. There isn’t a need for it.

‘My experiences over the year is that the old attitude, “I don’t mind if you’re gay but don’t rub it in my face” has actually generally held true. People nowadays, thankfully, don’t really care if you’re gay. But if you’re promoting sexual activities in public then it will put people off.’

How does he feel about those who accuse him of having internalized homophobia?

‘I refute that. It’s a social construct to divide ourselves. I’m an openly gay man. I marched in Prides back in the 80s and was kicked out of the Royal Navy for being open about my sexuality. I “came out” in 1984 and spent a week in prison, simply for being gay.

‘People will name call and insult simply to shut others up. They do so with no knowledge of the people they are talking to and make wild assumptions about them without knowing their outlook or history.

‘I think insults only hurt if they contain an element of truth. When people call me names I am not generally bothered because I know them not to be true.

‘It’s the same as “check your privilege”. It actually makes me chuckle. If they who say it had walked a mile in my shoes then they would think differently.’

People line the parade route in Toronto in 2017 (Photo: David Hudson)

’Without corporate sponsorship, there wouldn’t be the capacity to hold a Pride’

However, not everyone is uncomfortable with the corporate presence.

‘I get that lots of people feel it has been ‘corporatised’ but after more than 30 years of protesting for our rights and better representation it’s brilliant to see so many companies actively promoting their LGBT credentials,’ countered Facebook user Nigel Hall.

Unsurprisingly, festival organizers will point to the fact that most Pride festivals simply wouldn’t exist without corporate sponsorship.

‘The average Pride attendee supposedly donates 23p to their local event, and when some Prides can cost well over £150,000 to produce, this level of donation (as welcome as it is) would not cover the costs and put an incredible strain on the charities that run them,’ says John Bird, Co-Chair of Liverpool Pride in England.

‘Many large businesses or corporations wish to support Pride events for different reasons, some wish to make a difference, some wish to visibly be seen to support the LGBTQ+ community, some have grounded roots within those communities. Whatever the reason, sponsorships in the thousands of pounds cannot be shrugged off or taken lightly.

‘The majority of Pride governing bodies will be selective of who sponsors their events due to what the association with certain organisations may bring, and most sponsors only have involvement when it comes to their brand representation and how they can help and support.

‘The idea of “corporate sell out”, in my opinion, is “fake news”, as they do not dictate how the event is produced. This will solely rest upon the Pride teams themselves – yes, there will be certain contractual obligations, but nothing to extent of Pride no longer being Pride.

‘In short, without corporate sponsorship, there wouldn’t be the capacity to hold a Pride in many circumstances.’

Utah Pride (Photo: Utah Pride | Facebook)

3. It can provoke anxiety

It might surprise some, but many people who avoid LGBTI festivals do so because they avoid any situations with big crowds.

‘I have anxiety and severe body issues, so I prefer not to put myself in a place where I can so easily compare myself with people,’ said Jason Gray in London.

‘I have anxiety now, and being around heaps of people in one place would send me into panic mode… Pride is a great experience though … I had good times at pride back in my day!’ says Debbie Ford.

‘The large crowds and heat are sometimes barriers for me,’ said Lana Wolf.

‘I have depression and a Pride Parade has too many potential triggers, so I avoid going to avoid a possible crisis,’ says Grégory Damaso.

‘It’s just too busy for me,’ says Courtney Nunn, who has autism.

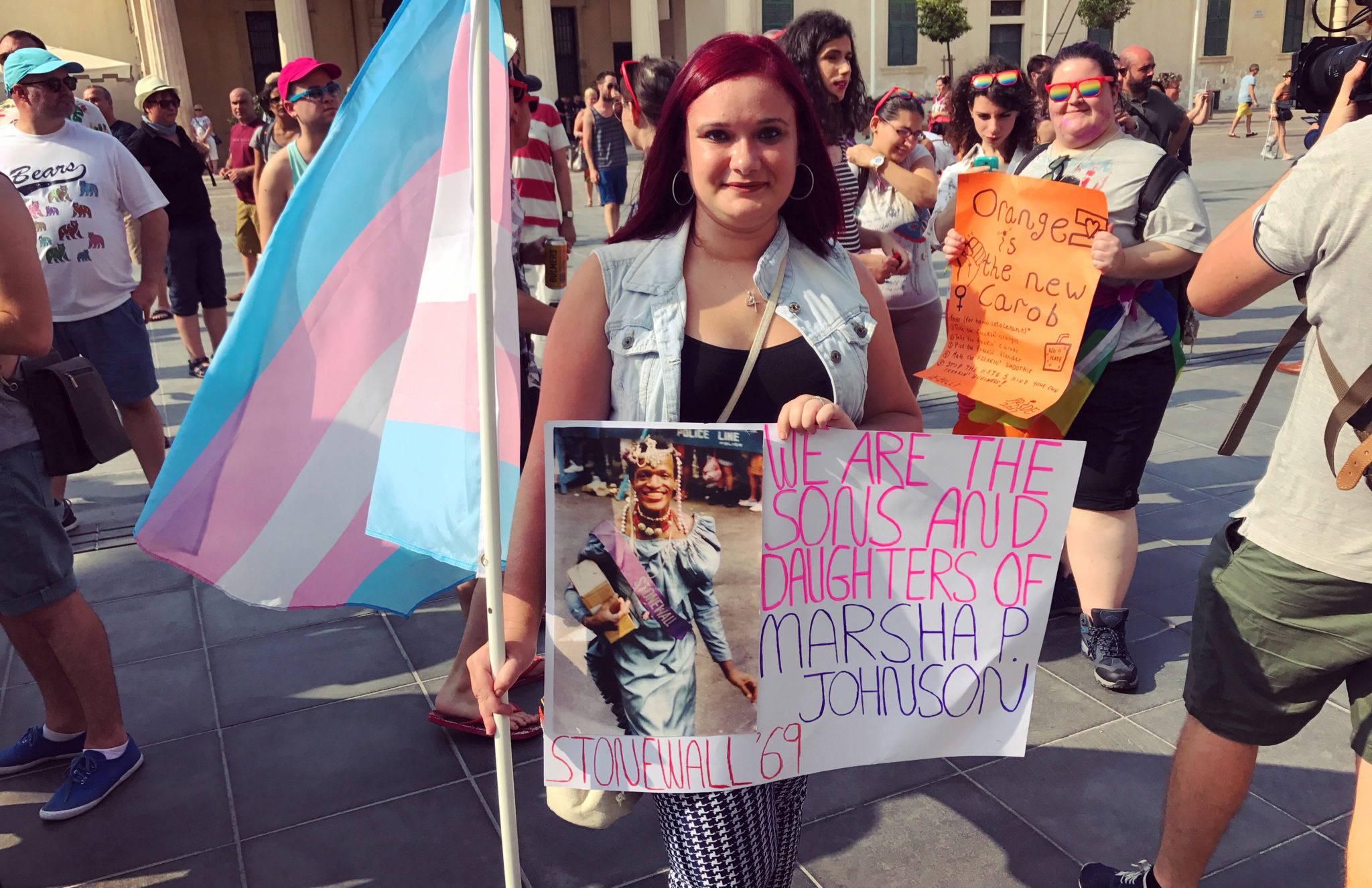

Honoring those who have gone before (Photo: David Hudson)

4. It doesn’t feel like it’s for me

Some people don’t like Pride because they don’t feel that they fit in – or wouldn’t appear to fit in.

‘Because despite being the ‘B’ in LGBT, I only really got to grips with that a couple of years ago. I was exclusively straight before that and am very much straight-passing,’ says Alex Dickson.

‘I’m a big supporter of Pride in general but I’d feel very much like I was insulting people who’ve actually faced homophobic discrimination and struggled with their sexuality by showing up as though I’m somehow part of a community born from adversity I’ve never actually faced.’

‘To be honest, when I think of attending Pride, I feel like it’ll be a place where I don’t belong. I’m pansexual and genderfluid in a het relationship with four kids. And as involved as I am in my LGBT community, I would feel like an outlier,’ says Francesca Beauchamp-Hartz.

‘It seems to be built for white, cisgender, gay, males and their business partners, while only allowing everyone else to tag along,’ says Alison Demzon.

Pride in London, 2017 (Photo: David Hudson)

5. I’ve already done my bit/too old to attend

Some people feel too old or unable to attend because of age-related challenges.

‘I would be anywhere for Pride but health and 65 seems to have taken its toll,’ says Connie Wilcox.

‘I attended the NYC parade from 77-84 and the parades were wonderful,’ says Sandi Rohrig.

‘It was only a few years after Stonewall. There were so many people, tens of thousands, curb to curb from the top of 42nd Street all the way down 5th Avenue to Washington Square. I moved to California in 85 and went to the SanFran parade in 86. It was wonderful.

‘I moved to St Petersburg [Florida] in ’90 and went to the Tampa parade and was very disappointed in the turnout. After attending parades that were hours long with 500,000 marchers, Tampa’s 20 min parade was a shock to the system. I’ve been to a few parades in St Pete in recent years but it’s not fun anymore.

‘I’m 69 now and it’s too damn hot for me … let the kids have fun. I’ve done my marching and protesting over the years and I’m done.’

Birmingham Pride, England, 2017 (Photo: David Hudson)

7. Attending can be dangerous

And lastly, in certain countries, participating in Pride can carry personal risk. Beirut Pride – a week long series of low-key events and performances – was forced to close by authorities last month and its organizer arrested.

Far-right groups have openly attacked Pride festivals in Eastern Europe, while police turned water cannons on people trying to hold a Pride parade in Istanbul in 2015. An attempt to hold a pride event in Mauritius earlier this month was cancelled due to safety concerns.

‘I don’t know about other countries but in my country, it is still very much needed. Here it is still a march and this year, it had to be cancelled because of religious bigots. There were so many death threats. My country needs it,’ says Kate Ng.

If you don’t want to attend your local Pride parade, check out whether it also runs associated arts or social events. These might be smaller, quieter and more to your liking.

And if you don’t feel that your local festival is relevant to you, how about seeing if you can show support for a Pride in one of those countries where such events act as an essential coming together for local LGBTI voices? A Pride event due took place at Kenya’s largest refugee camp earlier this month – largely thanks to the international support from a crowdfunding campaign.

See also

Why you should quit complaining Pride doesn’t represent you if you never bother to attend