In 2012 I was forced to flee my native Jamaica for my husband’s country of Canada.

It was all triggered when a Jamaican newspaper published an article about my marriage. They published an unauthorized photo of our wedding on their front page with the caption: ‘Jamaican Gay Activist Marries Man in Canada’. I immediately started receiving a flood of vicious death threats.

At the time, I was teaching law at a local university. And one of my students proceeded to post my teaching schedule and a description of the car I drove as a comment to the online article.

I was devastated and felt both betrayed and scared. I thought that I could not return to teach at that university for the upcoming semester, because my safety was so compromised.

Of course, I had no faith in the Jamaican police. After all, they had previously ignored my other requests for help in investigating death threats associated with my activism for LGBTI human rights on the island.

10 years hard labour for being gay in Jamaica

Although most of my students had probably suspected that I was gay, I had never confirmed their suspicions. Among other things, Jamaica criminalizes all forms of male-sex intimacy.

The penalties are severe. They start with a maximum sentence of 10 years at hard labour.

And once released, the persecution continues. You are required to register as a sex offender and always carry a pass. If you do not, you face a JA$1million ($7,500 €6,420) fine plus up to a year imprisonment for each offence of not having their pass.

Around the same time, fear-mongering right-wing Christian extremists sponsored a constitutional amendment banning same-sex marriage. During that debate, a Canadian law lecturer testified before Jamaica’s Parliament about the supposed ‘threat’ that same-sex marriage posed to society, based on the experience of marriage-equality in Canada.

I was devastated to have to leave my job teaching law, which I thoroughly enjoyed. Even more, I feared that by fleeing I had let the homophobic bigots win.

I was largely a prisoner while I was on the island

I was also teaching discrimination law to the President of Jamaica’s Senate. And I wanted to ensure that at least one of our senior politicians knew the truth about discrimination faced by the country’s LGBTI community.

So, after a month’s absence, I decided to fly to Jamaica every week from Toronto to continue teaching my courses for the rest of the semester. My husband strenuously objected. But as a former Toronto Police officer he helped me devise a security protocol to protect myself. It meant I was largely a prisoner while I was on the island, but it worked – I stayed safe.

At the end of the semester I relocated permanently to Canada and I was soon teaching law at another university.

At that institution I had none of the restrictions that plagued me in Jamaica about expressing my sexuality or discussing my husband, who also taught at the university. And I revelled in this new sense of freedom.

I was the first gay black teacher he had encountered

However, soon after I begun teaching I noticed a student (who I soon discovered was originally from Trinidad) staring sternly at me in class. He rarely smiled, and I thought my open discussions of my sexuality offended him.

Up until April of this year Trinidad was one of the last remaining countries in the western hemisphere that criminalized same-sex intimacy. Moreover, anti-gay religious sentiment was popular among Trinidadians.

But this student’s stares did not deter me. After all, I knew that in Canada the law protected from harassment.

It turns out that I could not have been more wrong about this Trinidadian-Canadian student. At the end of the semester he handed me a note. In it, he confided that he was himself gay, and that I was the first gay black teacher that he had encountered. He said my example had also inspired him to come out to his family and friends.

His disclosure left me speechless and humbled and we eventually became Facebook friends.

‘I felt like I would be alone if I came out’

He recently sent me another note that was again very moving:

Hi Maurice,

I hope that you and Professor Decker [my husband] are doing well.

Just wanted to give you a quick reminder that people all over the world are inspired by the work that you do. When it gets difficult, and I’m sure it does, remember that you offer enough light to lead many of us out of the darkness.

I didn’t come out till I was 30. A Conservative Baptist family and straight homophobic friends made it very difficult for me. I felt like I would be alone in the world if I did.

When I walked into the first class that I had the privilege of being taught by you in my first year of university I saw someone that I wanted to be like. A strong, well educated, well spoken, funny, gay black man. You gave me that inspiration and courage that I needed to send out an email to my friends and family a few weeks later.

Please continue to do what you do. We need you more than you know.

The sodomy law in Jamaica drives HIV rates

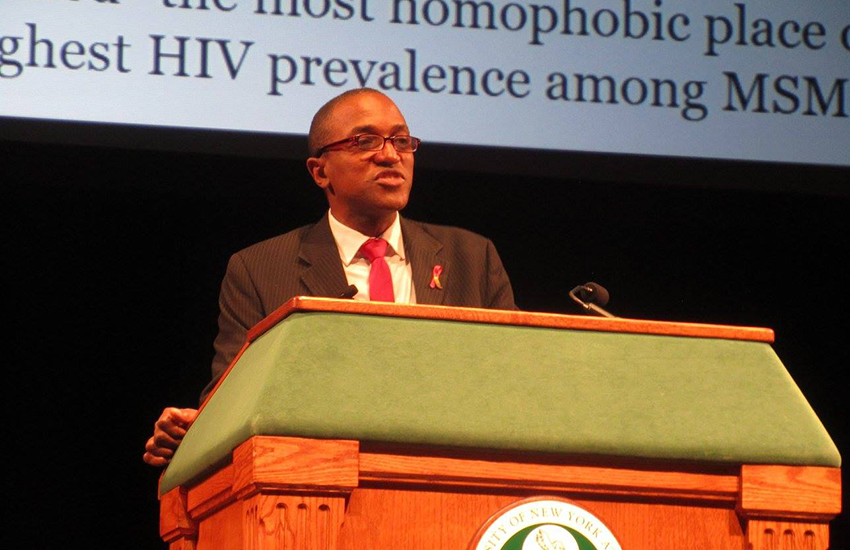

I have since left that university and now work full-time with the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network. There I lead the organization’s efforts challenging anti-gay laws and policies in the Caribbean.

These archaic British colonially-imposed statutes contribute to the region having the second-highest HIV prevalence rate worldwide after sub-Saharan Africa.

Jamaican men who have sex with men (MSM) also have the highest HIV prevalence rate in the western hemisphere, if not the world, 33%. The country’s draconian anti-sodomy law and the homophobia it engenders drives MSM underground, away from effective HIV prevention interventions.

Initially I represented a claimant in a legal challenge to Jamaica’s anti-sodomy law. But when he dropped the case because of death threats that he and his family received, I decided to take his place. I opted to use my privilege of being able to leave Jamaica to ensure that this critical matter did not die.

The case is before the country’s Court of Appeal and awaiting a judgment (due today, 31 July) on whether the country’s Public Defender can join in supporting my claim. Ten anti-gay religious groups gained permission to be in the case to oppose me.

Fighting anti-gay laws around the Caribbean

In addition, I am working with local partners in other Caribbean countries to challenge similar anti-sodomy laws. For example, on 6 June we filed a case in Barbados. There, the anti-sodomy law is the worst in the western hemisphere, with life imprisonment.

We are also sponsoring Caribbean Pride events, we train police in LGBTI sensitivity. And we even try to get religious groups talking about inclusion. These are among various other initiatives we use to change hearts and minds, as well as anti-gay laws.

All this work will require an investment of significant resources to help the Caribbean jettison its largely imported legacy of homophobia. We have therefore launched a ‘Caribbean Can Rainbow Fund’ so that global allies can join us in this incredibly important work.

As my Trinidadian-Canadian student taught me, the Caribbean LGBTI liberation work will have positive ripple effects even in the global north because: ‘Until we are all free, we are none of us free.’

Gay Star News is helping Maurice Tomlinson’s work by supporting Barbados Pride and Montego Bay Pride in Jamaica.

Also on Gay Star News

We have to stop this ‘stone the gays’ preacher visiting Jamaica