Indian teen influencer’s death spotlights toxic cyberbullying of LGBTQ folk: ‘people were telling me to die’

Priyanshu Yadav was a 16-year-old makeup influencer living in the central Indian city of Ujjain. An Instagram post dated November 12 showed him dressed in sari and decked in jewellery and makeup – a fitting outfit for the Hindu festival of Diwali that day. The post, however, attracted hundreds of hateful comments and even rape threats.

Nine days after that post, Yadav, also known as Pranshu, reportedly took his own life.

The tragic death shook the country’s LGBTQ community, putting a spotlight on the toxic and sometime deadly impact cyberbullying can have on queer youth.

Gay Indian content creator Shivam Bhardwaj. Photo: Shivam Bhardwaj

Queer individuals, rights activists and cyberbullying experts told This Week in Asia that India’s LGBTQ users face persistent online abuse, especially on Instagram and Facebook, despite the platforms promising to rein in such harassment. The outpouring of sadness over Yadav’s death has done little to stem the flood of hateful comments.

“I got a lot of hate after Pranshu’s death,” said Mumbai-based makeup influencer Shivam Bhardwaj, 25, who had posted a tribute video to Yadav on Instagram in which he had applied makeup as a way to process the grief and remember the teen.

“People were asking when I am dying and telling me to die in the [Instagram] comments. How can you wish that for someone?”

A 2023 social media safety index by the American LGBTQ advocacy organisation GLAAD found that platforms “continue to fail at enforcing the safeguarding of LGBTQ users from online hate speech”. While Instagram and Facebook – popular among content creators in India as TikTok is banned in the country – scored better than the previous year, the report said safety of LGBTQ users “remain[s] unsatisfactory”.

Despite the lack of India-specific surveys highlighting the extent of online harassment against LGBTQ users, anecdotal evidence and media reports underscore the trend. Bhardwaj and Yadav’s Instagram posts – the latter’s account is now private – are flooded with name-calling, homophobic slurs and comments encouraging self-harm.

Members of the LGBT community shout slogans as they take part in a pride walk in Siliguri in December 2022. Photo: AFP

More visibility, more abuse

Goa-based Durga Shakti Gawde came out as a trans, non-binary, gender fluid individual in 2017. But things turned ugly after they were featured in a video on gender fluidity the following year.

“I would get death threats, rape threats, acid attack threats, and saying they would kill my family,” said Gawde, adding they would receive about 200 to 300 abusive online comments daily on social media platforms.

That same year, India’s Supreme Court decriminalised Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which outlawed homosexuality. The landmark decision encouraged many LGBTQ individuals to live freely and own their identities online, as they took to various platforms to express themselves. In recent years, many have also used social media to endorse products and brands for commercial gains.

Both Bhardwaj and Gawde – who have over 22,000 and 40,000 followers, respectively – started proactively using Instagram around five years ago. Gawde uses social media “to express the things I needed to see when I was a kid”, including gender dysphoria, spirituality and biology. Meanwhile, Bhardwaj utilises it from a business perspective, endorsing fashion, beauty and lifestyle products, and to revolt against gender norms by wearing a skirt in public.

Both say they continue to receive hateful remarks through private messages and in the comments section.

‘Trauma, alienation’ still haunt LGBTQ Indians after end of gay sex ban: judge

‘Trauma, alienation’ still haunt LGBTQ Indians after end of gay sex ban: judge

Jeet, founder of LGBTQ advocacy group Yes, We Exist who only identifies with his first name, says queer people building a profession on creative fields requiring high social media presence are routinely bullied online. Name-calling is the most common form of hate speech, while there are also calls for violence towards the larger community, says Jeet, citing anecdotal evidence and his own research.

Over the years, change in laws and larger representation in India’s influential entertainment industry have given more visibility to LGBTQ people. Web series like Made in Heaven and commercial hits such as Badhai Do and Kapoor & Sons have made the public more aware of the queer community.

A 2019 survey from Pew Research Center showed 37 per cent of Indians believed the society should accept homosexuality, up from 15 per cent in 2013. Meanwhile, 53 per cent of respondents in another Pew survey published this year approved of legalising same-sex marriage.

But Jeet says such awareness has contributed to the spike in online abuse against LGBTQ folk.

“The further the queer discourse goes, the stronger the pushback is from the other end,” he said. “As more queer people are living freely, it might pose as a threat to others who can no longer bully them in physical spaces. So more people might be taking their frustration online because they can’t tolerate a young queer person.”

Whose responsibility is it?

India does not have a dedicated cyberbullying law, though there are various legal provisions involving harassment and stalking to counter online abuse. The country’s National Crime Records Bureau includes cyberstalking and bullying of women and children, as well as publication and dissemination of sexually explicit materials, in its annual crime statistics, but excludes naming the LGBTQ community.

Nirali Bhatia, founder of anti-cyberbullying organisation Cyber B.A.A.P., says LGBTQ individuals are targeted online due to their perceived differences, with body-shaming a common form of cyberbullying.

Bhatia, also a cyber psychologist and psychotherapist, says stricter and more comprehensive legal actions are needed to “deter bullies who currently perceive they can get away with their actions”, so that online spaces can be safer and victims are encouraged to seek help.

But activists say social media platforms also need to shoulder more responsibility in combating online abuse – and not just in English. India is home to several regional languages and dialects, which is also reflected in harassment online.

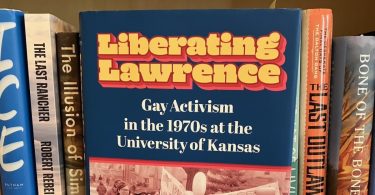

A screenshot featuring some of the hate comments in romanised Hindi posted under Shivam Bhardwaj’s tribute video for Priyanshu Yadav. Photo: Shivam Bhardwaj

Many such hateful comments in Bhardwaj’s tribute video to Yadav were in romanised Hindi, asking him to end his life and “get inspired” by the 16-year-old’s death. Yadav’s post also had similar comments in Hindi.

This year, Meta, which owns Instagram, launched the digital suraksha campaign and hosted a summit to promote online safety on its platforms. The company said it would support the Take It Down platform to counter online sexual abuse of young people, and the service would be available in Hindi and several regional languages.

Meta also said it had partnered with third parties to create online safety resources in more than five Indian languages to reach over 11 million people in the country.

However, many queer Instagram users and activists like Jeet accuse the company of not doing enough and “prioritising business over safety”.

“Their policies are very Euro-western centric, and they don’t realise what these words are,” Jeet said. “I doubt many queerphobic [Indian] slurs are actually in their list of banned words.”

Meta did not respond to This Week in Asia on its anti-harassment policy in regional Indian languages and the steps it was taking to combat abuse.

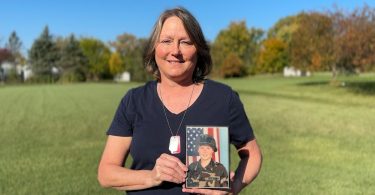

Aarti Malhotra and her son Arvey, who took his own life in 2022 after facing cyberbullying. Photo: Aarti Malhotra

Protecting queer lives: online and offline

In October, India’s Supreme Court fell short of legalising marriage equality, sparking debate on its “regressive” decision. Activists said such societal prejudice and inequality often emboldened people to be discriminatory online without fear of immediate consequences.

“Younger individuals are in a critical stage of identity formation,” said Bhatia from Cyber B.A.A.P. “They are more vulnerable to the negative effects of cyberbullying, and prolonged online harassment can contribute to mental-health struggles and increase the risk of suicidal thoughts.”

Aarti Malhotra, an educator and mother of a queer son who took his own life in 2022, knows the anguish firsthand. She said her 15-year-old son Arvey was harassed at school and online, and had to endure a slew of homophobic slurs in Hindi and other languages. The traumatic experience pushed him to death.

When Malhotra shared her experience on Instagram to raise awareness of queer issues after Arvey’s death, she faced similar harassment.

A screenshot of hateful comments in romanised Hindi posted on Aarti Malhotra’s Instagram account. Photo: Handout

Today, Malhotra runs the Arvey Aesthetics Foundation in memory of her son and offers guidance to minors and their parents who reach out to her, mostly through Instagram. She uses Arvey’s life as an example in her explanations about human sexuality and sexual orientation.

“I miss Arvey’s care and love so much,” she said. “I want to talk about this as much as possible so no one else has to experience what I went through.”

Activists say such conversations need to happen and their scope expanded beyond bullying, both online and offline.

Vikramaditya Sahai, a trans researcher and teacher at Delhi’s Ambedkar University, called for robust safety mechanisms to protect LGBTQ individuals both online and offline.

“If we are only going to fight when people on social media receive trolling, then I am sorry, we are creating the deaths we are mourning,” Sahai said. “If you want queer people to survive online bullying, they need to have a community to go to that gives them give care and comfort when they are afraid.”

More work ahead for India’s equality fight after ‘shock’ gay marriage ruling

More work ahead for India’s equality fight after ‘shock’ gay marriage ruling

Many queer social media users, however, say they do not have such safe spaces to turn to, citing the inaction of online platforms to counter abuse.

Bhardwaj believes it would be difficult for teenagers to handle online abuse without a shared community, just when they are in the tricky phase of exploring their identities. Bhardwaj said the bullying he suffered while growing up had made him think about ending his life.

“So I created that video for all those who are still alive,” he said, referring to his tribute video to Yadav. “It is heartbreaking that people were telling me – and also other queer content creators – to die because they cannot exist in the same world because I am gay. But we are not going anywhere.”