Contrary to popular belief, LGBTI people remain discriminated against in Peru, which has a total population of more than 32 million and of which an estimated 11 million lives in its capital, Lima.

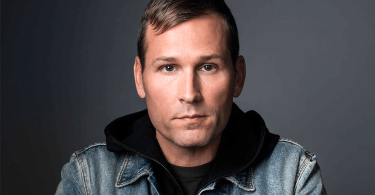

In the face of a strong anti-LGBTI political will that continues to perpetuate hate crimes committed against LGBTI people, I met Peruvian LGBTI activist Gabriel de la Cruz, who launched a new organization yesterday (28 June) to advocate for equality through the country’s media channels.

But the ultimate question has to be: why through media, and how will this new strategy pan out for the Peruvian LGBTI community?

De la Cruz is certainly no stranger to the media scene – the fervent independent activist launched a campaign #NoTengoMiedo (‘I do not have fear’ in English) with four other members as early as 2014, one that sought to collect stories from LGBTI Peruvians and have some of them share their stories on the theatrical stage – considered a first in the country back then.

In a course of three months, the campaign calling out for stories received 300 of them just in Lima alone – what resulted was the creation of a book detailing all these stories of LGBTI violence and their perpetuators, of which some were eventually chosen for the plays.

It can be seemingly hard to believe that Peruvians did not have much of a chance to know about the local LGBTI community before that – especially in this 21st century where media seems to have played a more pervasive role in our lives – but as De la Cruz shares more of the country’s history with me, I began to slowly assemble the jigsaw puzzle pieces together.

‘In the past, there was no portrayals of LGBTIs on the television. People did not have an understanding of what LGBTI is all about,’ says De la Cruz.

As I tried to further understand the reasons behind it, I recalled my own trip to Lima just a couple of months ago, where I saw long lines of Peruvians heading into the cathedrals around the city’s central plaza. Perhaps it might have to do with religion, or so I thought.

‘Peru is a very religious country. Before the country’s President gives his State of the Union address on Independence Day every year, he goes for a big mass organized by the Archbishop and which is well-attended by many politicians,’ De la Cruz shares with me as he confirms my own speculations.

He adds: ‘[The Archbishop] takes this chance [during the mass] to voice his disapproval of allowing same-sex marriage or abortion rights in Peru, and emphasizes on the importance of the family.’

‘Who really governs the country – the President or the church? I think it is the church,’ says De la Cruz.

It is then no wonder, that when #NoTengoMiedo was launched, its impacts were far-reaching – not only did it receive extensive media coverage by local journalists, some politicians requested to meet up with the organizing committee to understand the struggles faced by the local LGBTI community. According to De la Cruz, the politicians liked how the campaign took a non-violent approach to stand up for its cause.

On a broader scale, De la Cruz also shared with me that the campaign catalyzed the use of LGBTIs in the country’s subsequent music and cultural activities, sparked youth activism, and more importantly, encouraged young Peruvian LGBTIs to come out to their parents – having now seen that there are other Peruvians who face the same struggles as they do.

It is a fallacy, though, to think that Peru is well on its way to achieving LGBTI equality.

In a recent research conducted by market research firms, it was found out that 80% of Peruvians surveyed still reject the notion of same-sex marriage, 70% of those surveyed disapprove of civil unions, 75% dismissed the idea of adoptions for same-sex parents, and 65% of them having the opinion that legal protections for LGBTIs in the country are not needed.

In the same measure, this was perhaps what gave Fuerza Popular (Popular Force in English), the political party with the majority in the parliament, the confidence to vote against passing a bill to introduce legislation against hate crimes in the country earlier this year.

According to Peruvian non-governmental organization Promsex, there were a total of eight hate crimes, 43 assaults and 23 registered discriminatory acts in 2016.

The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) has also expressed concern that lives of LGBTIs Peruvians have been taken away against their wills, with the most recent one being a 14-year-old transwoman being shot four times in the head in May last year.

One of Promsex‘s studies in 2016 also showed that more than 70 percent of LGBTI Peruvian students surveyed feel insecure at school because of their sexual orientation and often suffer from verbal harassment, making it harder for their day-to-day classroom life. 58.3% had also expressed that they suffer harassment due to their gender identity and/or expression.

‘The politicians do not want to talk about something different that does not sit well with Peruvians. They need votes for the next election, so they will say what the Peruvians need to hear,’ De la Cruz shares.

He adds: ‘The parliament is rejecting any possibility to include us in the country’s Constitution.’

The numerous difficulties in pushing for change through legislative means have compelled De la Cruz to rethink his strategies. What has resulted is his intent to launch a new organization, named Presente (Present) on the 28th of this month to advocate for equality through the media instead.

‘[The organization] is going to have workshops in universities, to speak with journalism undergraduates about how incorrect terminologies influence LGBTI perceptions and perpetuate negative stereotypes,’ says De la Cruz, who explaining the inaccurate reportage in the media has played a big role in the lack of LGBTI progress in Peru today.

De la Cruz adds: ‘We also want to speak with the bosses of different TV channels, the most important form of media in my country, and tell them why it is important to teach their journalists about differences between members of the LGBTI community and the correct pronouns to use, especially for trans people.’

‘Lastly, we also hope to introduce LGBTI characters on screens, and raise awareness of hate and the need to live with diversity via television dialogues. Another idea is to put up photos of LGBTIs via street advertisements.’

The launch of Presente starts off with a networking event where members of the media and local social influencers have been invited. What is surprising, though, is that given the strong anti-gay sentiment in the Peruvian parliament, De la Cruz had also extended a launch invitation to the country’s Prime Minister, Fernando Zavala.

‘The Prime Minister’s sister, who was one of our ministers ten years ago, got married to another girl in Canada. Perhaps it is for that reason that he is an LGBTI ally,’ says De la Cruz.

However, De la Cruz is not hopeful that Zavala will be able to attend his launch.

He adds: ‘Fuerza Popular has the political power in my country, and they are not allies. The Prime Minister’s participation [in the launch] to talk about our rights might cause a situation where Fuerza Popular will try to remove him from his position.’

‘We have had instances in the past where Fuerza Popular changed the decisions of the President or his ministers because they do not agree. And they had removed ministers from office before,’ De la Cruz adds.

As Presente comes close to its launch, fans of the theatrical plays staged by #NoTengoMiedo need not be disappointed either. In fact, they may be able to expect more instead.

‘In September this year, I am also creating a new play named Congreso (Congress), as part of Presente,’ reveals De la Cruz.

He adds: ‘I will use all the arguments from the conservatives in the parliament against LGBTI people and incorporate them into this play. The day the parliament voted against the hate-crime bill was also the same day we heard of the setting up of the gay concentration camps in Chechnya, so I will do a parallel of what is happening in Chechnya and what is happening in Peru at this moment, to show how our situation is no different from theirs.’

With such a big change in strategy, I asked De la Cruz what he thinks his new organization’s chances of success will be.

‘I think the important challenge will be the conservative groups in society, because they are very strong and very well-funded,’ says De la Cruz.

He adds: ‘Their campaigns are very big, and as you know, for us we do not have so much funds. When I talk to the people here in Peru about LGBTI rights, I need to talk to 50 different people or groups to receive maybe three positive responses.’

De la Cruz, however, remains hopeful.

‘I know it is difficult, but I need to talk to as many people or groups as possible to form alliances with organizations who want to support our work or work with us – and I think I have done it before, so I hope I can do it again,’ says De la Cruz.

On a broader stroke, De la Cruz reveals his vision for his country, politically or otherwise.

‘In five or ten years’ time, I hope we will have a new parliament after this one finishes its current term. I really hope that more LGBTI people will run for parliament, and that the next mayor elections will have LGBTI people as candidates, and with these people in the government, or in companies, I hope we can change our reality,’ says De la Cruz.

He adds: ‘I hope the companies will also be more open to hire trans people as workers, and we can then start to talk about our LGBTI rights as a human right.’

Last month, I wrote a feature on Chile’s LGBTI activist Luis Larrain, who is running for political office in the country’s Congress at the end of the year.

(This story first appeared in The Santiago Times, in which Darius Zheng is also a special correspondent of. Darius is also an LGBTI activist who is currently based in Santiago, Chile. Permission has been obtained to share this story with Gay Star News as part of a monthly collaboration between GSN and The Santiago Times to feature the work of LGBTI activists from the Latin American region.)